Connecting with Celtic Spirituality

By Matt Shorten

In June 2019, ten Northeast American retreatants ventured across the pond to Achill Island, a wind- tossed haven on the westernmost coast of Ireland. Led by Rev. Sue Foster (Roger Solomon’s wife) and Rev. Maebh from the Sacred Path Retreat Center, our quest was to explore how the wisdom of Celtic spirituality might enlighten our daily lives.

Ireland is renowned as a beautiful and hospitable land, and one that has experienced terrible hardships and suffering, but at times, it’s also been the center of Western civilization and culture. Their deep spirituality can be traced back to Druidic traditions, centuries before the arrival of Christianity. Like the Shintaido founders, the Celts were focused on developing an organic relationship with nature and connecting with the grace in all of creation, asserting the life-affirming aspects of our elemental existence. In contrast to the Roman church’s dogma of “original sin,” the leaders there promulgated the notion of “original blessing”.

Although the North Atlantic winds there are strong enough to blow your chi away, the natives feel a powerful sense of alignment with the sacred earth and sky. It’s a good place to develop Ten-Chi-Jin. (Ten = heaven; Chi = earth; Jin = self)

In 563 Columba came to the isle of Iona and established the first monastery in Scotland. One of the earliest centers of Celtic Christianity, they practiced a radical gender-neutral egalitarianism, sometimes being led by a female abbess.

Influenced by the ancient texts of the Wisdom Tradition and the writings of St. John (he who listened to the heartbeat of Jesus), this movement resisted the authoritarian, hierarchical Roman Catholic Church as long as they could. According to legend, young warriors would spend their final year of training living in the gender role of the opposite sex to seek a more attuned balance of life.

J. Philip Newell writes “The passion of the Celtic mission lay in finding meaning in the heart of all life, a sense of wonder in relation to the elements, to recognize the world as the place of revelation, and the whole of life as sacramental. The western isles developed a rich treasure of prayers that referenced the sun, moon and stars as graces, and the spiritual coming through the physical. God is seen as the Life within all life. The Celtic crosses, triangulated knots, and illuminated texts incorporated designs that symbolized the interlacing of God and humanity, heaven and earth, spirit and matter.”1

I see clear parallels here with the mystical and anthropomorphic aspects of Shintaido. Aoki Sensei quotes sword master Sekiun to the same point: “We call the highest level which could be attained sei or “holiness”. This realm is yuiitsu muni- just as the sun is one and the moon is one. It is the highest and the holiest.”2

As Michael Thompson Sensei wrote in the Introduction to the Shintaido handbook, “Where does the body end and the mind or spirit begin? He (the budoka) is a specialist of that invisible and yet very physical part of ourselves which our doctors have not yet discovered. His ‘treatment’ is to teach us to communicate with our deeper selves, with each other, with nature and with God through the medium of our bodies”.3

One of the sacred practices we did on the retreat was to walk a stone labyrinth, situated on a peaceful hillside between a towering waterfall and a pristine sandy beach. Unlike a maze, a labyrinth has only one way in and one way out, but is nevertheless replete with surprising turns and discoveries. As one enters, you set an intention, and then just perform the movement with sincerity, trusting that when you finish, a clarity will arise upon emerging. Or as Aoki Sensei has said, “The locus of one swing of the sword is itself a sign”.4

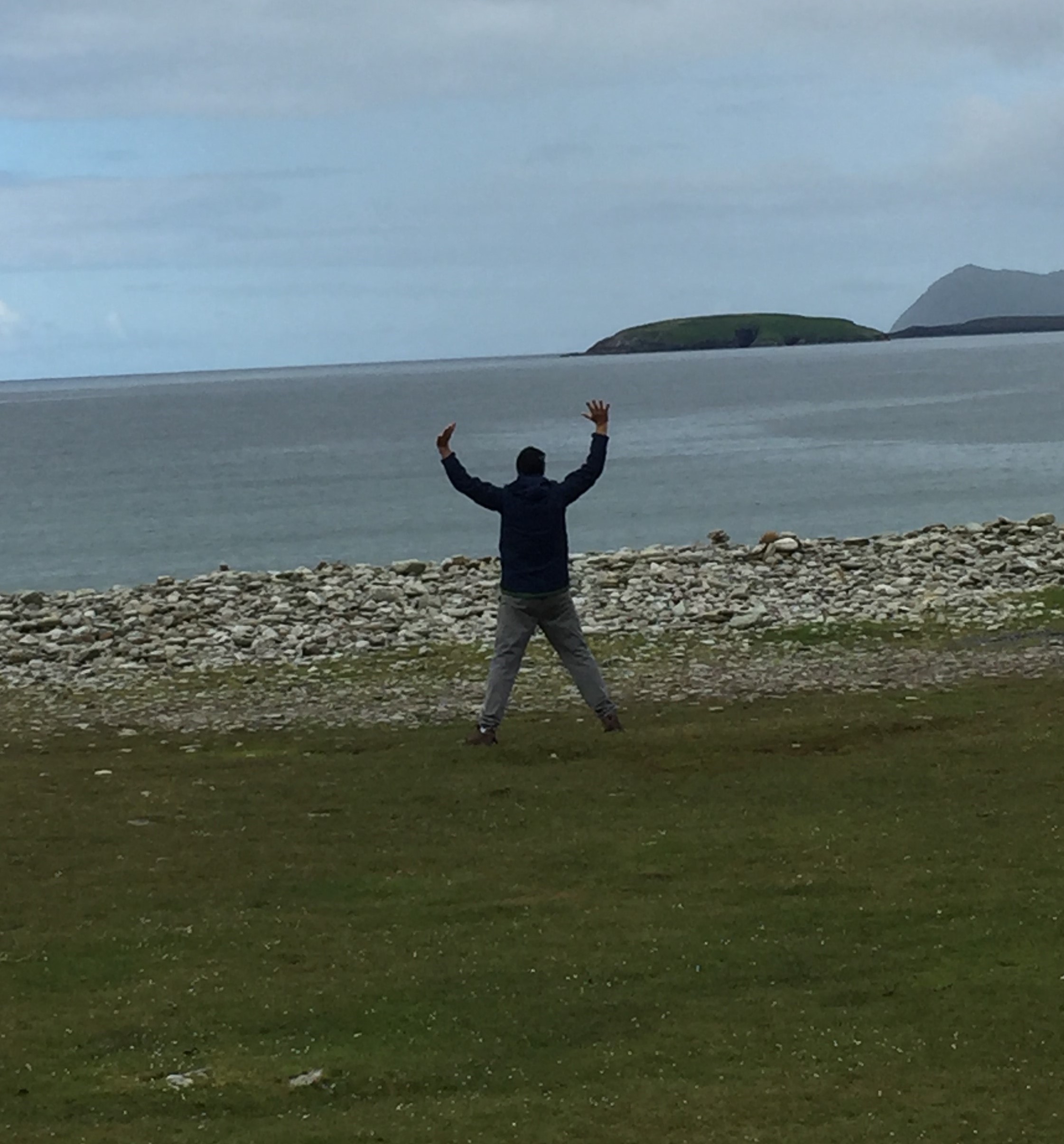

On the last day there, when our spirits were high, but our bodies restless after a long sitting meditation, I offered to lead the group in some uplifting movement. We did Ritsu-i-ju Meiso-ho (10-position standing meditation), wakame (seaweed), and aozora-taiso (blue sky exercise), all with beach and sky visualizations. Although some in the group were limited physically, our hearts were open to what was within and without.

1) J. Philip Newell, Listening to the Heartbeat of God, p. 3, Paulist Press.

2) Haroyuki Aoki, Shintaido, p. 31, Shintaido of America.

3) ibid, p. 12.

4) ibid , p. 35.