Once Upon A Time In Quebec City, Across Time And Space

By Lucian Popa

1995

I met Master Haruyoshi Fugaku Ito and his Shintaido in March 1995, in a yet frozen Quebec City. At the time I was 40 years old and had 20 years of karate training.

Shintaido means New Body Way. It was created by Hiroyuki Aoki and the Rakutenkai, a martial artists group he gathered in 1965. Before, from 1958, Aoki had been an assistant of Master Shigeru Egami, at the time head instructor of the Karate-do Shotokai.

As for myself, from the 1980’s I had been searching for a Shotokai karate-do instructor, but these were hard to find. In my search, I had been using these two names (Shintaido and Aoki) and, eventually, I got lucky. Sometime at the beginning of 1995, one of my friends – a young karate instructor whom I won over to Master Egami’s karate revolution – told me that he had found Shintaido in some martial arts directory. He talked on the phone to a Japanese person in California who he thought was Master Aoki. In fact, it turned out it was Master Ito, a top student of Aoki who answered the phone. He had brought Shintaido to America in 1975. To my friend enquiries, Master Ito said that, since he was going to teach a Shintaido seminar in Quebec City in March, and we could find out more by attending. So, an excited Paul Gordon called me with the news. I was thrilled and we decided to attend that workshop, though at the time, Paul was living in Fredericton, New Brunswick and I, in Toronto, where we had first met a few years earlier.

Returning to Master Egami and his book, I was very attracted by the author’s approach to the practice of karate-do and the deep spirituality I could sense behind his simple wording. So, from the early 1980s I began to change my karate training from the popular, widely accepted JKA sport style to that outlined by Master Egami in his book. This book got into my hands by luck, I’d say. An acquaintance received it from his father who worked abroad and bought it for his son. Knowing of my passion, he offered it to me. I still have it and read it over and over again.

With this new beginning, except for a few students that I had managed to win over, I was alone. The knowledge I had about these changes was general and restricted to the text of the book. Egami spoke of karate as a means of uplifting one’s spirituality by coming in contact with others, regaining human dignity and striving toward a state of body suppleness and natural power by reaching to the realm of vital energy laying beneath the limit of our physical/psychological strength.

Quebec City is somewhere halfway between Toronto and Fredericton. When the time came, I jumped in my old beaten-up Volvo and drove off. The seminar was to be held at L’Attitude, a massage school in downtown Quebec. On my way, in Montreal, I picked up an old friend and former karate student of mine who had expressed his wish to join us in this.

When we met, Master Ito presented us with the other, older book of Shigeru Egami,“Karate-do for the professional” of which 1,000 copies had been printed by the Shotokai. Following our request, Ito-sensei brought us this expensive and rare book featuring some 40 kata of karate and 4 kata of bojutsu (long staff) with black and white photos of Master Aoki performing these kata. Master Ito also appears in some of the pictures, and I still remember how, like two kids who had gotten a wonderful toy, Paul and I were sitting in the Kriegoff Cafe browsing through it and admiring the exquisite techniques of Master Aoki.

This seminar was dedicated to the massage practitioners of L’Attitude and was concerned with healing rather than martial arts. Friday night was more of a theoretical class about Amma/Shiatsu techniques and their Japanese names and meaning. Though we were not familiar with this massage and its terminology, we attended anyway especially because we learned that this was an integral part of Shintaido and that the martial art techniques and the massage techniques are the two edges of a sword. On our way in, at the front desk, we bought Master Aoki’s book “Shintaido, the body is a message of the universe” and were hosted in one of the rooms of L’Attitude.

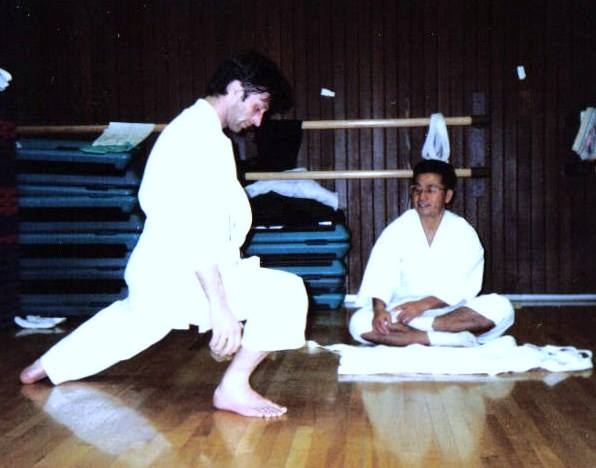

The first Shintaido class seemed weird to us and unlike any martial art we had seen before. We were doing light kicks holding hands in a circle, (a sort of French cancan), standing jumps led by the hands by a partner, the seaweed partnered exercise and some short, strange kata (Tenshingoso) standing in place and moving our arms with the hands wide open in large gestures resembling some of the movements in the traditional karate kata. We were shouting the five sounds of A, E, I, O and Um. Also, we did a lot of unusual partner stretching and running with expanded free hand cuts derived from sword practice. I was enjoying it though, at times, I was slightly put off by its new-age tang I felt and because I couldn’t find in it much of the karate imagined from the descriptions which I read in Egami-sensei’s book.

And yet, here and there in Master Ito’s classes, some of Master Egami’s lines were flashing before my eyes as I could link some of the things we were doing with his teachings. For instance, he advised that, in order to improve them, all movements should be done exceptionally large at first and cut down to size only gradually. I have always imagined a large movement as a much larger than a normal movement but in Shintaido the movements were extended even to the infinite by being performed moving the arms and hands slowly while at a full run, some two-three hundred meters or even more. Theoretically at least, one should never stop running and cutting. Most exercises were to be performed by opening the body joints, especially the pelvis area and the shoulders and letting go of all unnecessary tension.

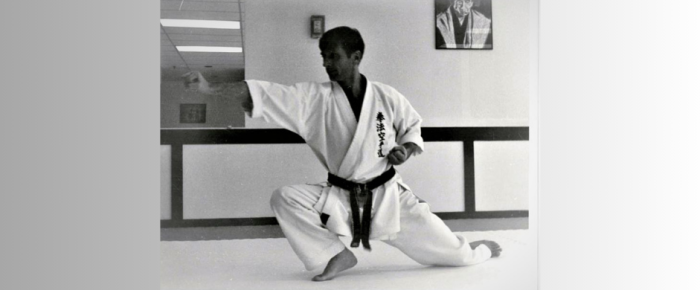

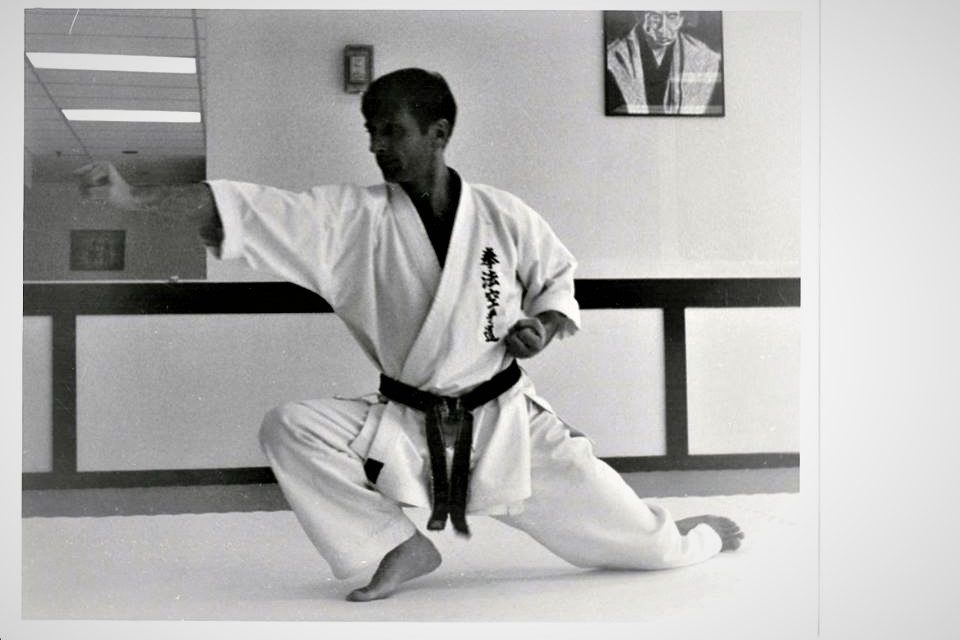

In the middle of all this, as if sensing we could be disappointed by all these imprecise, slacken looking and expansive movements, Master Ito took a very low stance – the Shotokai crouched stance – and did an Oi-zuki (stepping and lunging forward while thrusting out the fist on the same side with the advancing foot). He had been talking to someone just before doing it and his demo of the lunge punch might have been the result of the conversation he was having. But he saw us watching with a corner of his eye and I also supposed that, at this point, I had enough of running techniques and shouting and what not, and wondered if there was any real martial art movement in Shintaido. I thought he wanted to hook us in with this but I didn’t mind it because it was why we attended the workshop.

The step, the punch were one flash. Nothing like the Oi-zuki done in any other style, sluggish, stiff and delivered after the feet became stabilized, but a one solid, swift shift of mass with the one knuckle punch protruding ahead like a spearhead. I was much impressed with that thrusting punch that looked to me exactly like what Master Egami was talking about, starting and arriving together with the step.

I think it was some half an hour before the end of the last class when Master Ito asked the participants to take a rest as they were all pretty tired. Then, he turned to the three of us and said:

“Hey, karate kids, let me show you how I used to train under Egami-sensei!”

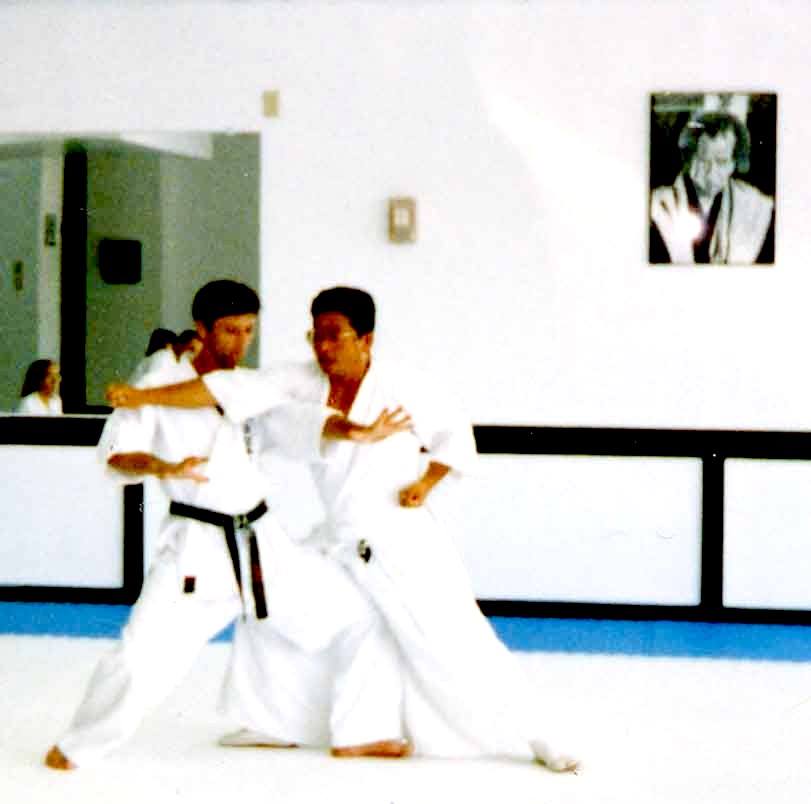

And he showed it to us indeed. First, we were asked to do punching in the horse-riding stance (Kiba-dachi) at his counting. On the surface there wasn’t anything different from the way we had been practicing before or the seiken choku zuki of other styles. That is, except the shape of the fist, the way we stood and we punched. The horse-riding stance is relaxed not tight and at least theoretically, as the fatigue grows the stance will get naturally lower by itself. You won’t stand up when getting tired like people do in the cramped stances of regular karate. Also, the one knuckle fist requires an upward bent wrist and that eases the tension in the wrist, elbow and shoulder allowing for smoother movement. And last, the body turns more with the punch and the shoulder joint opens instead of being locked back. In ten minutes, we were sweating and gasping for air mostly because we were too stiff and tense.

After this, it got harder. We were told to take kamae – en guard position in a front stance – with a lower-level block but, as Master Ito required of us, the stance was almost impossible. We were asked to virtually sit on our front heel which came off of the floor while the back leg and foot were struggling behind. It was crazy, I had never trained before in this so called koshi-dachi. Just imagine stepping forward from one stance to another. We had to lunge forward and punch holding this stance and, at one point, my friend from Montreal couldn’t take it anymore. He crawled outon all four. I remember sensei correcting the way I was doing the one middle knuckle fist by turning the fist out at the wrist. I got the feeling of a snaky arm right away and was thankful for it, it is the proper arm alignment when punching something that way.

Paul and myself kept going to the end of the half hour doing these crawling oi-zuki. When eventually I stood up, my heart was beating wildly in my neck – not long ago I had suffered a massive heart attack – and I must have said that to Paul who smiled and replied:

“Don’t worry, I feel the same!”

Conclusion

From my first encounter with Shintaido and Master Ito, nearly 30 years ago – our relationship still goes on today. I have learned the real skill is transforming conflict – its creed is “how to transform negative and destructive energy into positive and constructive energy.”

In order to do that, it is not enough to be able to beat others for the conflict will end only temporarily. He who wins by force has conquered only half his enemy someone said once. By facing your opponent squarely, one will surely make the statement that you are the enemy. According to the body wisdom of Master Ito stand or sit next to your enemy and reach some degree of agreement or cooperation which is already present in the two facing the same direction. From having developed force, one should proceed to the use of no-force. First to have and then not to have.

Master Minagawa replied to someone who, watched his demonstration and said “One needs a strong koshi” with “No, one doesn’t need a strong koshi, one needs a weak koshi.”

The use of no-force means to rely in an encounter mainly on your neuro-sensorial or efferent nervous activity. This way you will not create enemies. Mastering elements such as timing, space interval and energy flow belong to a higher level of skill and allow one to defeat the enemy without the damaging effects of brutal/animal fighting. I once asked Master Ito what he would do if he was attacked. His answer came quickly and spontaneously paraphrasing what Don Juan Matus gave to a young Carlos Castaneda:

“I will not be there.”

Biography

Lucian was born 8 December 1954 – In Brasov, Romania (at the time the city of Brasov was still called Stalin!)

He started his martial arts practice in 1969 with Judo and a little later Olympic free style wrestling until 1973.

He was in the military service (alpine troops) from March 1974 to July 1975.

He began to practice karate shotokan in the summer of 1975, right after the army service.

In 1980, he read Egami Shigeru « The Way of Karate Beyond Technique. » He decided to follow Egami’s approach and started his own group.

He arrived in Canada in 1989 and in 1992 worked for the Superkids Karate franchise as instructor at one of their locations. It was here that he met Paul Gordon and they became fast friends. The Superkids lasted for one year and in the fall of 1993 he opened his own dojo. Unfortunately, he had a massive heart attack that led to postponing the opening of the club until January 1994.

In March 1995, he met Ito Sensei and Shintaido and began to introduce it in his school.

His association with Shintaido as an organization lasted until 2007, when he participated in his last Kangeiko.

His health began to deteriorate, and he suffered a mini-stroke early in 2008. He remembered that 10 years prior he was briefly exposed to Dachengquan or Yiquan while visiting Romania.

He found that this practice was better suited to his condition than Shintaido, although he never stopped Shintaido totally, especially bojutsu and some karate. In 2012 he invited Master Ito to Romania and twice a year he would come and teach his group Shintaido Kenjutsu, until 2019. The next year the Covid came upon us and his seminars were interrupted.

He continues to develop a synthesis between the large and liberating Shintaido movements and the shorter, spring-like power envisioned by the Yiquan.