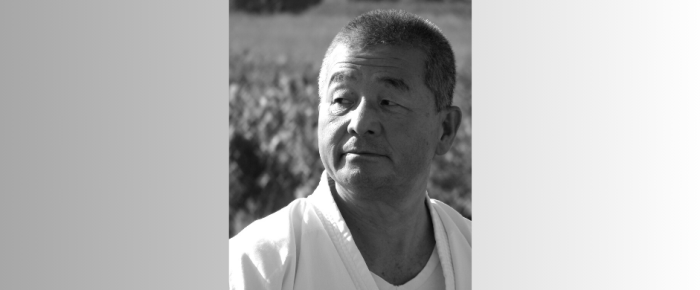

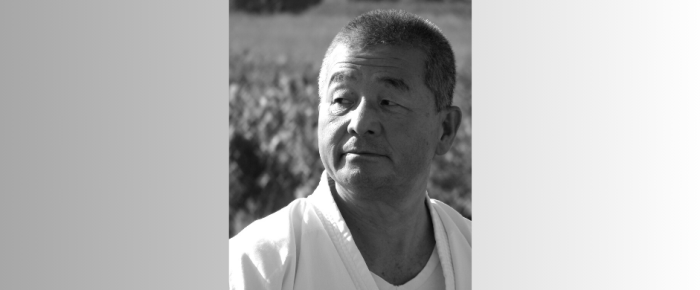

With great sadness, we announce that H.F. Ito died peacefully at home in Cuy, France on Dec 30, 2023. He was born in Hiroshima, Japan on May 23, 1942. He…

Read moreH.F. Ito Obituary

With great sadness, we announce that H.F. Ito died peacefully at home in Cuy, France on Dec 30, 2023. He was born in Hiroshima, Japan on May 23, 1942. He…

Read more

by Connie Borden

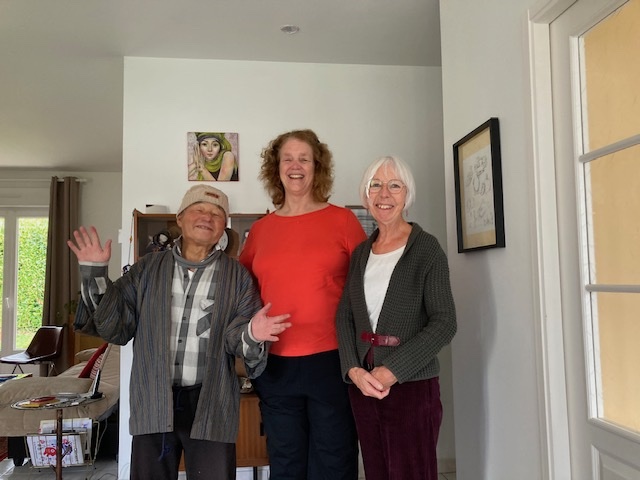

I travelled to France in early November 2023. HF Ito and Nicole Beauvois me for the first 5 days to enjoy their new house in Cuy France. The second half of the trip was to Limoges France to study Kenjutsu with Shintaido General Instructors and Yondan Kenjutsu Instructors Pierre Quettier and Mieko Hirano.

Cuy France is 90 minutes from Paris and near Sens and Troyes. We explored the Farmers Market in Sens and visited the majestic Cathedral. One day was spent exploring the historical section of Troyes France to see the architecture and have a splendid lunch at a French restaurant. I was fortunate to have a private lesson with Ito Sensei on Kenjutsu. Thursday afternoon, we did a Taimyo Keiko in honor of Brad Larson who recently unexpectedly died. Brad was a SOA Instructor and SOA Board Treasurer. The visit concluded with a dinner with friends of Nicole and Ito.

Limoges France, about 4 hours from Paris, was the site for the Kenjutsu workshop. During the past 2021 and 2022 workshops, they explored Shoden no kata and Chuden no kata. This year, our study was Okuden no kata, the third in the trilogy. Eighteen people attended this workshop. Pierre and Mieko hoped for attendees to “cultivate their garden of practice with complete peace of mind.” Practicing in person after time apart allowed us to do Kumitachi with a variety of partners while also sharing a little of the Shintaido « breath of eternity », as Pierre stated.

This year, in order to optimize the practice time on site, they offered preparation beforehand. I met with Pierre and Mieko by ZOOM to review my study of Kenjutsu. As a result, my homework for the 5 weeks before the workshop was to learn and study Goho Batto-ho, the 5 drawing techniques. I thank Robert Gaston and Sarah Baker for their time and guidance during these 5 weeks. Ito Sensei during my private lesson gave many instructions to refine my techniques with the focus to “keep your blade active”.

Pierre presented a website to support our personal practices and serve as support for the goreï of Kenjutsu teachers. Pierre offers this website as a resource: Shintaido Kenjutsu Cyberdojo.

The workshop started Friday November 10th with a collegial keiko and meal. During our practice we studied Goho Batto-ho, known as 5 drawing techniques either with Bokken or Shin Ken. Saturday, November 11 there were two keiko. We divided into 3 groups based on level of practice. Mieko Hirano instructed Group A on Chuden no Kata and the first two Jissen Kumitachi. Alain Chevet assisted Pierre in teaching Group B and Pierre guided the practice Group C. We systematically studied the movements of Okuden no kata, often doing kumitachi applications of the movements. The repeated practice brought the kata alive to give a glimmer of it’s meaning. We then set a goal to study #1 to #11 of the Jissen Kumitachi, however for most of us we achieved practicing the first five kumitachi.

In the evening we met to discuss the Kenjutsu curriculum. Pierre distributed his comprehensive documents on the Hagakure – the Trilogy of three kata (Shoden no kata, Chuden no kata, and Okuden no kata). We discussed teaching Kenjutsu, especially to the new students. The group of 18 people included Ula Chambers and Charles Burns from the UK, me from North America and students from across France. Many report the advantage of teaching Kenjutsu to reach new audiences.

Sunday, November 12 was keiko 3. We continued with Jissen Kumitachi, now attempting to review #12 to #22! The last part of our morning, we combined into one group so all could practice Dotoh and Ryuhi Kumitachi. Pierre led our group to demonstrate Okuden no Kata to Mieko’s group, then the full group did Shoden no kata and Chuden no kata multiple times to bring our movements and breath into synchrony. After a meal, and the typical Shintaido goodbyes of hugs and kisses, we departed around 2 p.m.

I am grateful to Pierre, Mieko and Alain for their teaching and dedication to Shintaido Kenjutsu. I enjoyed the opportunity for kumitachi or partner practice in this focused workshop. While the workshop was located in France, our Shintaido study is the same art. The facility in Limoges provided comfortable lodging along with excellent French cuisine.

By Rob Kedoin

On Sunday, November 12th, Shintaido members gathered at the Unitarian Church of Sharon for Brad Larson’s memorial service. The church was filled with so many people that some watched the service from an overflow location in the building. The service was beautiful. Rev. Jolie Olivetti spent time talking about Brad’s family as well as his many interests in Shintaido, Biodanza and drum circles. There was a period of sharing where people could tell stories of Brad. These stories ranged from his omnipresent smile to his involvement in the church, the Historical Society and his many contributions to the world of interactive storytelling in museums.

From a personal perspective, Gail and I began the day by hiking in the nearby Moose Hill Wildlife Sanctuary. I know how Brad loved to run with his boh or joh through the woods and while I have no idea if he ever ran the trails of Moose Hill, it helped me to envision being on trails he once traveled.

Toward the beginning of the service, the reverend relayed a message from Brad’s mother which affected me deeply, that, « Brad would be the first one to forgive. » I needed to be reminded about this because I had felt myself growing angrier and angrier about Brad’s death.

Matt Shorten spoke about Brad and Shintaido, then led us in Tenso and Shoko as we stood at the front of the church. David Curry then invited the attendees to join us in open handed Tenso and Shoko. Facing a church full of people, palms outstretched in Shoko, all sharing their love for Brad was awe inspiring.

For myself, I will always miss doing the standing back stretch with Brad. I always felt like I was being lifted like a rag doll and being stretched by a kind, gentle giant.

Brad once spoke to his church’s congregation about a three-rock meditation he learned from Thich Nhat Hahn. Since the congregation thought it fitting to send us away with packets of three rocks and the meditation directions, it seems like a good way to close. Hold each stone consecutively in hand:

Stone 1: Breathing in, I see myself as a flower; breathing out I feel fresh

Stone 2: Breathing in, I see myself as a mountain; breathing out I feel strong

Stone 3: Breathing in, I see myself as still water; breathing out I reflect things as they are

By Bela Breslau

Shintaido practitioners in New England were lucky during their October workshop.

We were lucky to study with Senior Instructor Lee Ordemann who came up from Washington DC and led two keikos on Saturday that focused on the Jissen Kumitachi program. It was new for most of us and a refresher for a few. We practiced with bokken during two keikos on Saturday. A big thanks to Lee for making the trip and sharing his expertise with us. Heather Kuhn arranged to rent space at the Guiding Star Grange in Greenfield, the perfect dojo with a high ceiling and wood floors.

As New Englanders who have experienced the rainiest of falls, we were also lucky on Sunday morning when we gathered at Unity Park in Turners Falls. The sun came out just as we started, creating a dramatic backdrop. Bela led a Toitsu-Kihon and Eiko curriculum and encouraged everyone to express their energy and knowledge next to the beautiful Connecticut River. At least one practitioner (Eva Thaddeus) kept saying the field was her new favorite outside dojo. At the end of class, Stephen led us in Reposada, a new short kata developed by General Instructor Jim Sterling. “Reposada” means “restful “ in Spanish. It provided the perfect way to close.

In addition to the nourishment of learning from Lee and practicing the tried and true with Bela, we had two wonderful meals together: a potluck on Saturday night at Stephen and Bela’s house, and a breakfast and closing at Heather’s apartment in Turners Falls on Sunday morning.

Here’s a link to pictures from the weekend. You’re sure to recognize Margaret Guay, supreme organizer for the group, plus Lee, Bela, Stephen, Ann, Matt, Eva and Heather.

Bela and Stephen were delighted to host Lee and the women in his life – his lovely wife Elizabeth and his beautiful and energetic three-year-old daughter Esme.

By Lucian Popa

1995

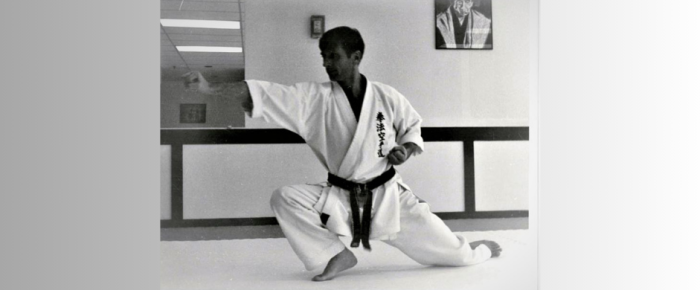

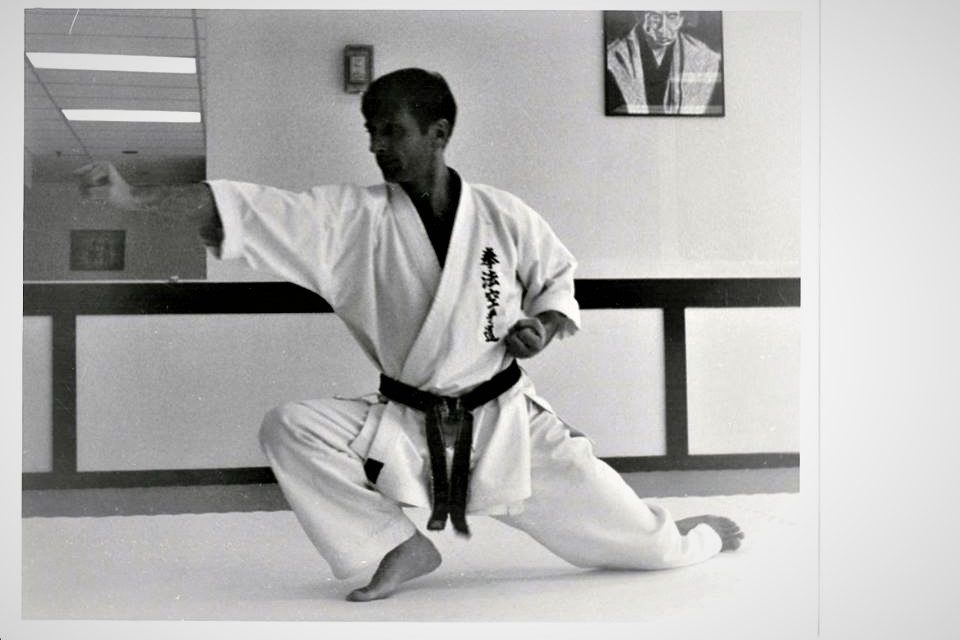

I met Master Haruyoshi Fugaku Ito and his Shintaido in March 1995, in a yet frozen Quebec City. At the time I was 40 years old and had 20 years of karate training.

Shintaido means New Body Way. It was created by Hiroyuki Aoki and the Rakutenkai, a martial artists group he gathered in 1965. Before, from 1958, Aoki had been an assistant of Master Shigeru Egami, at the time head instructor of the Karate-do Shotokai.

As for myself, from the 1980’s I had been searching for a Shotokai karate-do instructor, but these were hard to find. In my search, I had been using these two names (Shintaido and Aoki) and, eventually, I got lucky. Sometime at the beginning of 1995, one of my friends – a young karate instructor whom I won over to Master Egami’s karate revolution – told me that he had found Shintaido in some martial arts directory. He talked on the phone to a Japanese person in California who he thought was Master Aoki. In fact, it turned out it was Master Ito, a top student of Aoki who answered the phone. He had brought Shintaido to America in 1975. To my friend enquiries, Master Ito said that, since he was going to teach a Shintaido seminar in Quebec City in March, and we could find out more by attending. So, an excited Paul Gordon called me with the news. I was thrilled and we decided to attend that workshop, though at the time, Paul was living in Fredericton, New Brunswick and I, in Toronto, where we had first met a few years earlier.

Returning to Master Egami and his book, I was very attracted by the author’s approach to the practice of karate-do and the deep spirituality I could sense behind his simple wording. So, from the early 1980s I began to change my karate training from the popular, widely accepted JKA sport style to that outlined by Master Egami in his book. This book got into my hands by luck, I’d say. An acquaintance received it from his father who worked abroad and bought it for his son. Knowing of my passion, he offered it to me. I still have it and read it over and over again.

With this new beginning, except for a few students that I had managed to win over, I was alone. The knowledge I had about these changes was general and restricted to the text of the book. Egami spoke of karate as a means of uplifting one’s spirituality by coming in contact with others, regaining human dignity and striving toward a state of body suppleness and natural power by reaching to the realm of vital energy laying beneath the limit of our physical/psychological strength.

Quebec City is somewhere halfway between Toronto and Fredericton. When the time came, I jumped in my old beaten-up Volvo and drove off. The seminar was to be held at L’Attitude, a massage school in downtown Quebec. On my way, in Montreal, I picked up an old friend and former karate student of mine who had expressed his wish to join us in this.

When we met, Master Ito presented us with the other, older book of Shigeru Egami,“Karate-do for the professional” of which 1,000 copies had been printed by the Shotokai. Following our request, Ito-sensei brought us this expensive and rare book featuring some 40 kata of karate and 4 kata of bojutsu (long staff) with black and white photos of Master Aoki performing these kata. Master Ito also appears in some of the pictures, and I still remember how, like two kids who had gotten a wonderful toy, Paul and I were sitting in the Kriegoff Cafe browsing through it and admiring the exquisite techniques of Master Aoki.

This seminar was dedicated to the massage practitioners of L’Attitude and was concerned with healing rather than martial arts. Friday night was more of a theoretical class about Amma/Shiatsu techniques and their Japanese names and meaning. Though we were not familiar with this massage and its terminology, we attended anyway especially because we learned that this was an integral part of Shintaido and that the martial art techniques and the massage techniques are the two edges of a sword. On our way in, at the front desk, we bought Master Aoki’s book “Shintaido, the body is a message of the universe” and were hosted in one of the rooms of L’Attitude.

The first Shintaido class seemed weird to us and unlike any martial art we had seen before. We were doing light kicks holding hands in a circle, (a sort of French cancan), standing jumps led by the hands by a partner, the seaweed partnered exercise and some short, strange kata (Tenshingoso) standing in place and moving our arms with the hands wide open in large gestures resembling some of the movements in the traditional karate kata. We were shouting the five sounds of A, E, I, O and Um. Also, we did a lot of unusual partner stretching and running with expanded free hand cuts derived from sword practice. I was enjoying it though, at times, I was slightly put off by its new-age tang I felt and because I couldn’t find in it much of the karate imagined from the descriptions which I read in Egami-sensei’s book.

And yet, here and there in Master Ito’s classes, some of Master Egami’s lines were flashing before my eyes as I could link some of the things we were doing with his teachings. For instance, he advised that, in order to improve them, all movements should be done exceptionally large at first and cut down to size only gradually. I have always imagined a large movement as a much larger than a normal movement but in Shintaido the movements were extended even to the infinite by being performed moving the arms and hands slowly while at a full run, some two-three hundred meters or even more. Theoretically at least, one should never stop running and cutting. Most exercises were to be performed by opening the body joints, especially the pelvis area and the shoulders and letting go of all unnecessary tension.

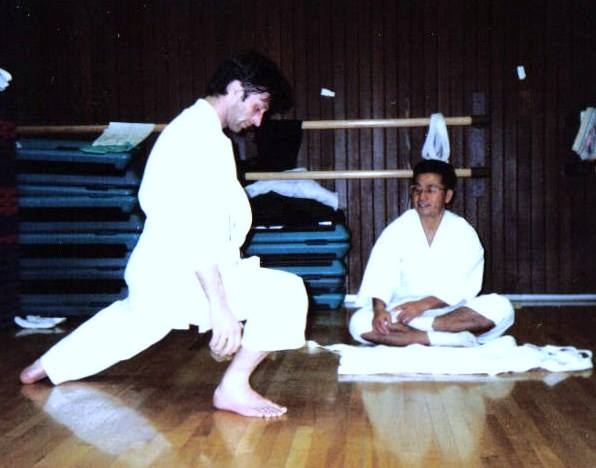

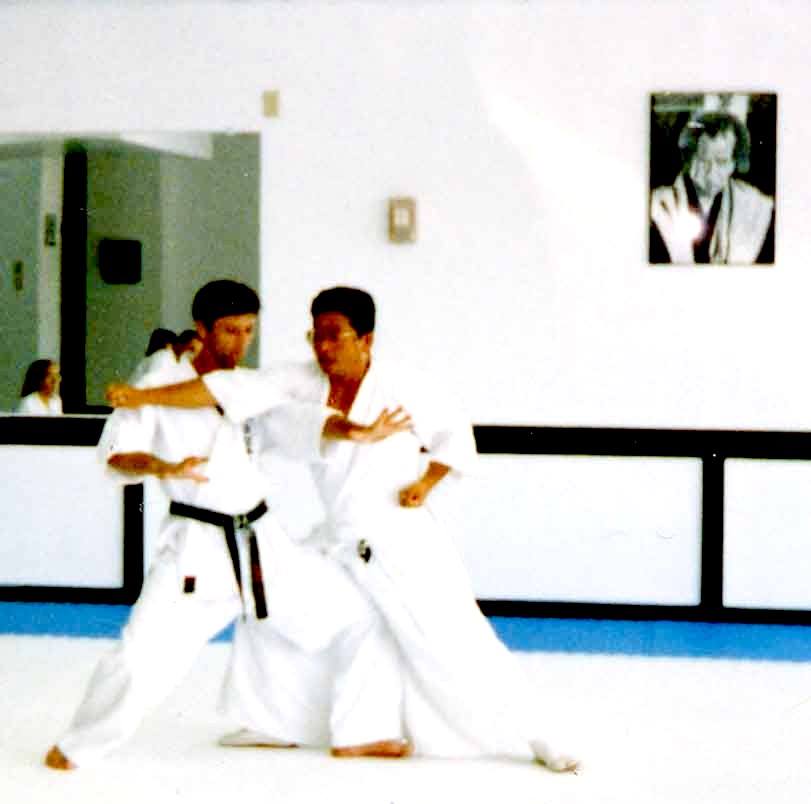

In the middle of all this, as if sensing we could be disappointed by all these imprecise, slacken looking and expansive movements, Master Ito took a very low stance – the Shotokai crouched stance – and did an Oi-zuki (stepping and lunging forward while thrusting out the fist on the same side with the advancing foot). He had been talking to someone just before doing it and his demo of the lunge punch might have been the result of the conversation he was having. But he saw us watching with a corner of his eye and I also supposed that, at this point, I had enough of running techniques and shouting and what not, and wondered if there was any real martial art movement in Shintaido. I thought he wanted to hook us in with this but I didn’t mind it because it was why we attended the workshop.

The step, the punch were one flash. Nothing like the Oi-zuki done in any other style, sluggish, stiff and delivered after the feet became stabilized, but a one solid, swift shift of mass with the one knuckle punch protruding ahead like a spearhead. I was much impressed with that thrusting punch that looked to me exactly like what Master Egami was talking about, starting and arriving together with the step.

I think it was some half an hour before the end of the last class when Master Ito asked the participants to take a rest as they were all pretty tired. Then, he turned to the three of us and said:

“Hey, karate kids, let me show you how I used to train under Egami-sensei!”

And he showed it to us indeed. First, we were asked to do punching in the horse-riding stance (Kiba-dachi) at his counting. On the surface there wasn’t anything different from the way we had been practicing before or the seiken choku zuki of other styles. That is, except the shape of the fist, the way we stood and we punched. The horse-riding stance is relaxed not tight and at least theoretically, as the fatigue grows the stance will get naturally lower by itself. You won’t stand up when getting tired like people do in the cramped stances of regular karate. Also, the one knuckle fist requires an upward bent wrist and that eases the tension in the wrist, elbow and shoulder allowing for smoother movement. And last, the body turns more with the punch and the shoulder joint opens instead of being locked back. In ten minutes, we were sweating and gasping for air mostly because we were too stiff and tense.

After this, it got harder. We were told to take kamae – en guard position in a front stance – with a lower-level block but, as Master Ito required of us, the stance was almost impossible. We were asked to virtually sit on our front heel which came off of the floor while the back leg and foot were struggling behind. It was crazy, I had never trained before in this so called koshi-dachi. Just imagine stepping forward from one stance to another. We had to lunge forward and punch holding this stance and, at one point, my friend from Montreal couldn’t take it anymore. He crawled outon all four. I remember sensei correcting the way I was doing the one middle knuckle fist by turning the fist out at the wrist. I got the feeling of a snaky arm right away and was thankful for it, it is the proper arm alignment when punching something that way.

Paul and myself kept going to the end of the half hour doing these crawling oi-zuki. When eventually I stood up, my heart was beating wildly in my neck – not long ago I had suffered a massive heart attack – and I must have said that to Paul who smiled and replied:

“Don’t worry, I feel the same!”

Conclusion

From my first encounter with Shintaido and Master Ito, nearly 30 years ago – our relationship still goes on today. I have learned the real skill is transforming conflict – its creed is “how to transform negative and destructive energy into positive and constructive energy.”

In order to do that, it is not enough to be able to beat others for the conflict will end only temporarily. He who wins by force has conquered only half his enemy someone said once. By facing your opponent squarely, one will surely make the statement that you are the enemy. According to the body wisdom of Master Ito stand or sit next to your enemy and reach some degree of agreement or cooperation which is already present in the two facing the same direction. From having developed force, one should proceed to the use of no-force. First to have and then not to have.

Master Minagawa replied to someone who, watched his demonstration and said “One needs a strong koshi” with “No, one doesn’t need a strong koshi, one needs a weak koshi.”

The use of no-force means to rely in an encounter mainly on your neuro-sensorial or efferent nervous activity. This way you will not create enemies. Mastering elements such as timing, space interval and energy flow belong to a higher level of skill and allow one to defeat the enemy without the damaging effects of brutal/animal fighting. I once asked Master Ito what he would do if he was attacked. His answer came quickly and spontaneously paraphrasing what Don Juan Matus gave to a young Carlos Castaneda:

“I will not be there.”

Biography

Lucian was born 8 December 1954 – In Brasov, Romania (at the time the city of Brasov was still called Stalin!)

He started his martial arts practice in 1969 with Judo and a little later Olympic free style wrestling until 1973.

He was in the military service (alpine troops) from March 1974 to July 1975.

He began to practice karate shotokan in the summer of 1975, right after the army service.

In 1980, he read Egami Shigeru « The Way of Karate Beyond Technique. » He decided to follow Egami’s approach and started his own group.

He arrived in Canada in 1989 and in 1992 worked for the Superkids Karate franchise as instructor at one of their locations. It was here that he met Paul Gordon and they became fast friends. The Superkids lasted for one year and in the fall of 1993 he opened his own dojo. Unfortunately, he had a massive heart attack that led to postponing the opening of the club until January 1994.

In March 1995, he met Ito Sensei and Shintaido and began to introduce it in his school.

His association with Shintaido as an organization lasted until 2007, when he participated in his last Kangeiko.

His health began to deteriorate, and he suffered a mini-stroke early in 2008. He remembered that 10 years prior he was briefly exposed to Dachengquan or Yiquan while visiting Romania.

He found that this practice was better suited to his condition than Shintaido, although he never stopped Shintaido totally, especially bojutsu and some karate. In 2012 he invited Master Ito to Romania and twice a year he would come and teach his group Shintaido Kenjutsu, until 2019. The next year the Covid came upon us and his seminars were interrupted.

He continues to develop a synthesis between the large and liberating Shintaido movements and the shorter, spring-like power envisioned by the Yiquan.

by Tomi Nagai-Rothe

I led a group in meditation/worship at the beginning of a gentle movement workshop for Friends.* Without thinking, I took the group of 18 people into Um. After the session a participant came up to ask, “Is this group especially good at getting into deep meditation?” I remember thinking “That’s just Um.” I didn’t want to take too much credit, but I mentioned that it’s possible to lead a group into a deep meditation.

Friends spend a great deal of time in silence: it’s a familiar place to be. We also try to be attentive to those around us. That is where keiko and Friends’ culture overlaps. It hadn’t occurred to me how attentive to gorei a group of Friends could be.

In July I traveled to Western Oregon University in Monmouth, Oregon to lead a five-day workshop (2.5 hours per day) entitled, “Gentle Movement for Traumatic Times.” The workshop was inspired by two F/friends who had survived serious illness and were unable to find accessible movement classes. Beyond that, I had heard many stories from Friends of the Global Majority who had been traumatized by insensitive interactions with white/European-American Friends. I wanted to both create a welcoming space and to share traditional martial arts tools from Shintaido to work with stress and conflict.

Over the five days I shared Panic/Rock/Wakame/Bamboo solo and with partners; Wakame kumite; Soto Irimi – stepping in; Sagari Irimi – dubbed “Welcome, This Way Please” by Ito; Tenshingoso and a simple leading/following kumite.

I shared Panic/Rock/Wakame/Bamboo as options for addressing stressful interactions. The main point was knowing when to let things go and go with the flow (wakame) or to stand firm (bamboo). People had a chance to think about situations in which they wished they had had these tools, and current situations in which they could practice them.

I was really glad that everyone took to kumite so quickly and took good care of their partners. It makes me think that I don’t often consider the deep opportunities that kumite really offers. It really can be a door to liberation that I cannot access alone.

I knew I wanted to share Soto Irimi – simply stepping in and changing the plane of one’s body to be closer to an attacker. In the 1990s I was working closely with a talented woman I call my mentor/tormentor. I learned strategy from her and much more, but she moved fast, was intense and had huge demands. Eventually, I felt like she was coming at me full speed like a freight train. One evening I told this story to Lee Seaman in my kitchen and she had me stand up and pretend that she was my tormentor. She said, “Try stepping in.”

Stepping in and changing the plane of my body made all the difference. That practice helped me survive the next three years. I no longer felt like I had to be plastered by someone coming at me.

Everyone quickly connected with their partners and we practiced with just one step. During the debrief one person shared that their health care provider had demonstrated a stepping back technique that they had used to engage in a conflict, but that stepping in hadn’t even occurred to them. They asked themselves, “How could I make use of that in my situation?” they asked themselves.

I talked about and demonstrated – with my F/friend who was a great demo partner – how being in close is safer and not at all threatening to the other person: it’s simply in close and connected.

Then we moved on to a form of Ushiro Irimi that Ito calls, “Welcome, this way please.”

This 7 second video show me and Connie Borden demonstrating it. Ito describes this as going to the front door to greet a visitor, then opening the door and guiding them inside. I especially love this kumite.

Perhaps it’s because I was so incredibly slow to be able to demonstrate it. It took me years. In fact, Ito tried using different names, taught it several times in the Bay Area, and organized a workshop that I later realized was specifically for me! I was able to teach this to people who had no martial arts experience in a few minutes, so I think I finally get it.

During our debrief I shared what Ito says about literally sharing the same perspective as your opponent, standing shoulder to shoulder – and the game changing attitude of welcoming the person who is attacking.

I think it was hard for Friends to understand the value and importance of a sincere attack: Friends tend to be conflict averse (or passive aggressive!) so tsuki was a bit challenging.

During one of our large group conversations there was a long silence and the group naturally dropped into worship sharing — a time during which people can speak out of the silence on a particular topic. It was wonderful that everyone was so comfortable with silence – not something I ever experienced as a meeting facilitator since groups expect a meeting to be filled with talk.

It was fascinating to navigate across my experiences of meeting facilitation, gorei and worship leading – especially when these distinct practices overlap.

One big takeaway was how tiring it is to undertake a gasshuku without the support of a director of instruction or any sensei care. Outside of Shintaido and Japanese culture, no one thinks about such things. I did just submit a proposal to offer the workshop again next summer and this time I will make sure someone comes to support me! Stay tuned for a Body Dialogue update next year.

*Religious Society of Friends (also known as Quakers)

by Connie Borden and contributions by Rob Gaston, Sarah Baker & Peter Furtado (the Daienshu reporter)

Thirty-three people attended the British Shintaido Daienshu 2023 held at Worth School from the 18th of August to the 20th of August 2023. Daienshu literally means “great maneuvers” and was the name given to the annual Gasshuku of the Sogo-budo Renmei (the transition organization from Shotokai karate to Shintaido and means “federation for a holistic martial art”). Worth Abbey is home to a small community of Benedictine monks. Worth School is an independent school in Turner’s Hill, W. Sussex UK. This event, led by Masashi Minagawa and managed by Charles Burns with the assistance of Viola Santa, represented new life.

As Charles Burns explains about the theme: “Shinsei (new life) allows us to look beyond the darkness of our turbulent times to find the hope that new life always brings. Joy, community, and our encounters with one another are all strong themes in our Shintaido world. Let’s imagine and experience new possibilities in our own lives, while enjoying the opportunities presented by a new venue for our ongoing practice.”

Prior the Daienshu, Robert Gaston, Connie Borden and Sarah Baker traveled to Scotland and the UK for 10 days. We are grateful to the hospitality of Nagako Cooper, Ula Chambers, Pam & Masashi Minagawa and Charles Burns for the extended time in Shintaido community. We practiced Taimyo, Shintaido, Bojutsu and Kenjutsu over these 10 days. We enjoyed the countryside around Dumfries Scotland, a river cruise in Shrewsbury UK and then taking a thermal spa in Bath!

Durning our travels we took many trains and climbed even more stairs, Fitbit not required. Some trains were fun, some were cumbersome, and some were rather stressful as we learned the ropes, but all got us to where we were heading, generally in one piece, if not worn out by more stairs. Also, for our traveling enjoyment, there were a few words of wisdom to live by which were frequently repeated, least we should forget: “Mind the Gap”, “Mind the Step”, and “See it, Say it, Sorted” (the latter referring to unattended baggage, of course right? I mean who wants unattended baggage left not sorted out?).

When we arrived at the Daienshu we were joined by other SOA members: Laura Sheehan- Barron with her husband Ted Barron and David Franklin. Our Daienshu experience was rich with 3 keiko plus two morning sessions and a special invitation to the British Shintaido College keiko and exams. The opening meeting started and ended with a long, low, resonant blast on a huge conch from Jackie Calderwood.

Master Instructor Masashi Minagawa was the instructor for the BSC keiko and three keiko in the Daienshu. Minagawa sensei shared in the BSC Keiko his insights into diamond 8 practice giving clear stepping sequence to go along with diamond 8 sei. Friday evening keiko was in the sports hall to the sounds of British rainfall outside. This first Keiko began with joyful warmup by Ula who had all laughing and relaxed. Minagawa sensei emphasized making and restoring strong connection since it has been some time since such a large and International group of shintaidoist have come together. Many stayed to practice long after keiko ended.

Our two morning keiko were outdoors under oak trees with a view of the green golf course. Nagako taught the first morning session on Taimyo Part III and Ula taught the second morning session on Diamond 8 Sei and Dai.

The Daienshu reporter Peter Furtado states:

“The second keiko (Saturday morning) began with some vigorous tsuki and Eiko, before moving onto kumite, receiving tsuki attack with Tenshingoso applications, and receiving jodan attack with mai irimi and yoko irimi. Building on yesterday’s Ma exercises, Masashi stressed the importance of settling or grounding as you receive the attack, and before sending the partner on their way.

The (Saturday) afternoon session was entirely taken up with exams – which ranged from 9/10 kyu boh and karate exams, to nidan bohjutsu and kenjutsu. The entire session was very impressive, the examinees were all seriously committed, and the nidan kumite, in particular, both skillful and spectacular. Watching was a great opportunity for the newer members to see what their practice might lead to one day, and for older members to revisit their prejudices? about exams.”

Congratulations to all who passed their examinations!

A party on Saturday night included being bathed in sound from the gong played by Jackie Calderwood. Masashi Minagawa explored the possibilities of sonic calligraphy, tracing the characters Do-Kan (way of the circle – the theme of next year’s International) on the gong. Carina hosted our party and Terry played the guitar while we joined in singing. Ula led us in dancing.

As Peter Furtado further reports:

“Early Sunday morning was just as bright, but somewhat dewier, than Saturday, as Ula led us in Diamond Eight Cutting under the trees. But by the time the final keiko began, in the outdoor dojo, dark clouds had appeared and the keiko was interrupted with short showers that made us move under the trees. The extensive kumite – wakame, more Tenshingoso applications – built on the previous two keiko, before we picked up our bokken and practiced kyukajo.

Building on all this, the keiko finished with a rare treat – genuinely spectacular and moving demonstrations by the ITEC members of key features of the keiko (and incorporating some exam feedback): Gianni Rossi showing tsuki, Tenshingoso and boh kata; Charles Burns and Rob Gaston showing neriai; Ula Chambers and Connie Borden kyukajo; and finally David Franklin and Gianni Rossi doing a typically free and powerful kiri oroshi kumite. Everyone watching knew that they had seen something very special, and had been given a unique gift, an intimate vision of what Shintaido can really be in the hands of committed practitioners.”

A strong ma lasted throughout the gasshuku and is continuing to maintain its presence in a vigorous dialogue on WhatsApp. During the closing ceremony, diplomas were distributed, sharing of experiences occurred and enthusiasm for returning in 2024 was said by all. Gratitude was expressed to the organizers and sensei. Jackie closed out the meeting with the blowing of the conch.

Here are some additional comments

Robert Gaston – There was a sense from the start of the Daienshu that the trees grew higher, and their roots deeper, over the course of our gasshuku.

Sarah Baker – Through the height of Covid we learned new ways of connecting using Zoom and other video resources. In those times seeds were planted as we all worked to continue to connect. In meeting together New Life has begun to sprout and take hold. Let us stay connected, however we can, and see what comes.

Connie Borden

Masashi Minagawa reflected the theme of « New Life » translates into his teachings. Teaching Shintaido movements in ways that are accessible and beneficial to the practitioners. His teaching such as Kiroroshi no kumite is to go far enough with the technique to find a person’s center and by going through Ten to reach « just the tipping point » that results in change. The goal of rolling is not the goal, the goal is to change your partner with just enough technique to be effective and nothing extensive that might be too harsh for your partner to appropriately receive.

Feeling inspired to join the community? Then consider attending the International 2024 being held in this same location from 16 August 2024 to 20 August 2024. As Peter Furtado reports:

“ The site is vast, green, orderly, and peaceful, with wonderful outdoor dojos and fabulous spaces for morning Taimyo; a large sports hall . . .and a huge dining room where we were offered huge school-food portions supplemented by a salad bar.”

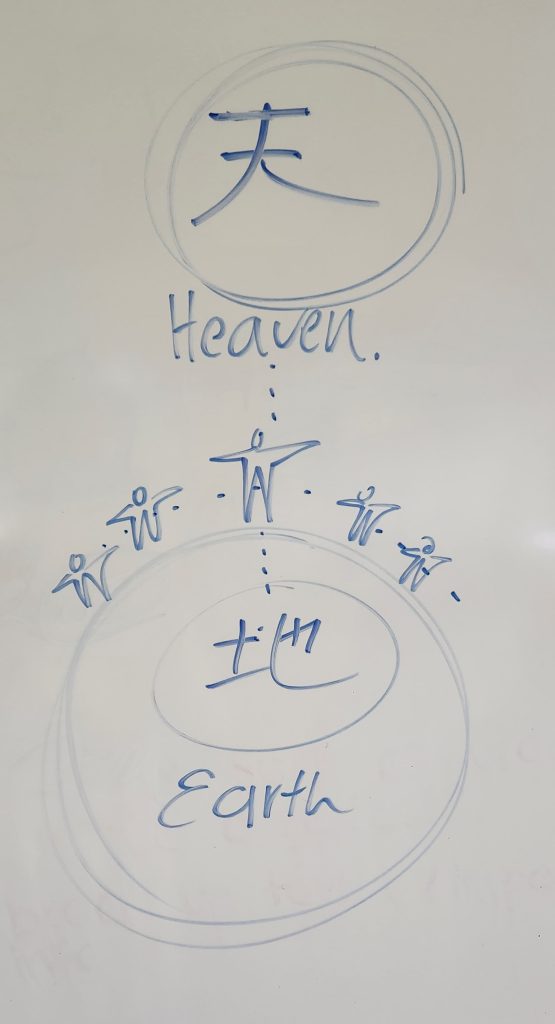

by H.F. Ito

edited by Lee Seaman and Tomi Nagai-Rothe

Mourning

A number of people close to me have passed away recently: my wife Nicole’s brother Philippe Beauvois, my friend Jim Cummings who was a business partner with my friend and colleague John Kent – in addition to my cousin in Japan.

Nicole and I started a morning/mourning ritual to remember them and to pray for their souls. We also hope this will help them in their passage out of this life. According to Buddhist tradition, there is a long “tunnel” called the bardo that the soul must travel on its way to Nirvana. It takes 49 days and during that time the soul may become attracted to and side-tracked by episodes related to their karma. This is why relatives and friends pray for 49 days to help the soul emerge from the tunnel without getting stuck. Nicole and I have been doing that for Philippe, Jim and my cousin.

During our ritual we listen to the Dalai Lama chanting the Maha Mrityunajaya Mantra.

16 years ago, I envisioned Eiko Dai cosmology as a Kaiho-kei approach to passing through the bardo. My own fusion of morning mourning is a Yoki-kei approach. I use Master Ma’s Tai Chi warm-up – goboho kenko (五防保健功 – literally “five ways of maintaining your health”) in addition to Yoki-kei Tenshingoso (天真五相).

Yugen

Noh classical Japanese theater is very dramatic, very old, and full of symbolism. In Noh the main character often comes out center stage, and then another character shows up. It reminds me of a person walking in the woods and suddenly meeting a ghost. Usually we think of ghosts as scary, but in this case the main character isn’t frightened at all. The ghost is often someone who has passed away and begins sharing their regrets, so the main character and the ghost end up talking. The ghost shares everything about its life regrets (almost like counseling or psychotherapy) and then it disappears.

Zeami, the founder of Noh, talked a great deal about yugen (幽玄) – a fundamental Noh Theater concept. Yugen means “profound grace and subtlety.” It is one of the three ancient ideals underlying Japanese culture and aesthetics. Zeami said it’s almost impossible for young Noh actors to express yugen on stage: they must reach a certain level of maturity before they understand it. To me the concept of yugen is deeply related to these ghosts in Noh theater. It seems obvious to me now, but I don’t think I could have understood that when I was a young man.

I have often led celebrations of life for Shintaido friends and students who have died including Bill Peterson, Juliette Farkouh, Christophe Bernard, Anne-Marie Grandtner, Joe Zawielski, and John Seaman. When I did those, the feeling was very Kaiho-kei, strongly expressing my ki energy for them. But now when I do the morning mourning ritual, it is Yoki-kei, more resilient and receiving. For me, Yokikei keiko is essentially an expression of yugen.

During our morning rituals Nicole and I often saw Philippe, and just as in the Noh drama, we weren’t frightened. In fact, it seemed very natural. Behind Philippe, we saw Nicole and Philippe’s parents. It felt like time travel – connected to an alternate reality. Rather than frightening, it was a pleasure and a comfort. No separation between this world and the other world.

Epilogue

Shintaido comes from the martial arts and when I was younger, I talked a lot about life and death when I was teaching. But I never actually thought about death being beside me during keiko. It wasn’t until I began to learn diving that I realized how close death is: one tiny mistake can be fatal when you are diving. So that really changed my teaching of Shintaido. I learned to have much more real-time respect for life and death. And though death is scary, it wasn’t like that when Philippe came with his parents. It was more like, “Wow!”

I started my 49-day morning mourning ritual with Philippe’s death, but in the middle of it Jim died, and then my cousin, so the 49-day rituals stacked up and extended out in time.

And now I feel, “Okay, I can keep going with this meditation for those who pass away before me!” Until the end of my life . . .

Acknowledgements – Many thanks to Lee Seaman and Tomi Nagai-Rothe who helped me put these experiences into words.

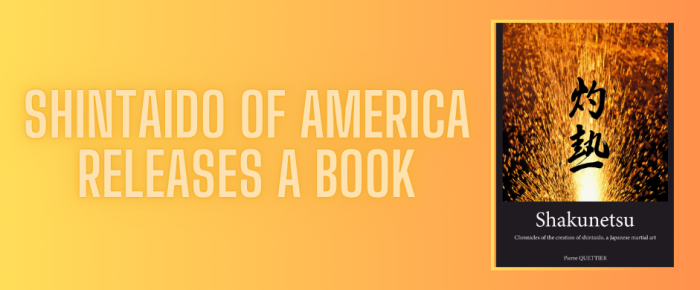

Shintaido of America (SOA) is honored to announce the release of the English version of Shakunetsu; Chronicles of the Creation of Shintaido, a Japanese Martial Art. The goal of this collective biography is to provide the stories of many who studied Shintaido in the 1960’s and 1970’s. Pierre Quettier, author of the book, shares his academic analysis of these interviews.

Shakunetsu was first released in French in January 2022. In October 2022 the board of SOA agreed to sponsor the efforts to release an English version of this book. A group of five, Peter Furtado, Nancy Billias, Lee Seaman, Lee Ordeman, and Pierre Quettier guided by the coordination efforts of HF Ito, undertook the editing and proofreading of the English version.

First let’s understand the time and setting when the creation of Shintaido was being developed.

Pierre Quettier, Shintaido General Instructor, author, and sociologist states:

“In the extraordinary burst of the sixties, a group of young Japanese idealists embarked on a quest typical of the time: to break down the cultural and class barriers of the venerable budō to bring the essence to the greatest number. They founded Rakutenkai, the « society of optimists », then, in 1975, a brand new discipline, Shintaïdō.”

Peter Furtado, Shintaido Senior Instructor, Journalist, and historian writes in the foreword:

“This unique book is complex in its ambition and structure. At its heart is the raw material of history – it brings together the oral testimony of 19 Rakutenkai members who describe in their own words how they came to join, what they were seeking and what they found. But this is supported, and given meaning, by the more academic commentary of sociologist and shintaido instructor Pierre Quettier, who carefully places their testimony in the contexts of the Japanese martial and other arts, and of the youth culture – in Japan and around the world – of the time, which had many similarly grand ambitions to change the world, though taking a different path up the mountain. He also offers a personal, honest, and sometimes painful account of the process of meeting the contributors and assembling the texts. As a social scientist who takes the name of that discipline seriously, he sticks closely to the evidence he has collected, declining to conjecture or judge, and refusing to repeat myths unless they can be grounded in fact. In the introduction, he explains the physically and emotionally arduous – and extended – process of preparing this work.”

HF Ito, Master Instructor, and co-founder of SOA remembers how important he felt about having these biographies collected from Rakuntenkai members:

Some time at the beginning of 2000, I got a call from Pierre Quettier who wanted to interview the former Rakutenkai members, who devoted their young lives in order to create Shintaido founded by Master Aoki during the ‘60s~’70s, I immediately understood his intention as a sociologist!I remembered there was a series of documentary films produced by NHK, in which the directors collected stories of many Japanese engineers, scientists, & entrepreneurs who worked behind scenes, in order to encourage & rebuild the Japanese industry, economy, and technology which were crushed by the events of WW II. The title of this program was “Project X”. So, this is how I started to work together with PQ to publish a book, later named “Shakunetsu! »

Pierre Quettier describes his enthusiasm for this academic project:

“Having studied ethnology . . ., now holding a teaching-research position at the University of Paris 8 and well versed in biographical methods in the social sciences, I decided to take up Bernard Ducrest’s historical project as my own and to initiate a process of collecting life stories of the Rakutenkai members. H.F. Ito was enthusiastic about it and in 2002 I obtained a small budget from the head of my service at the university; with it H.F. Ito and I traveled all over Japan to interview the members one by one.”

Members of the project team who spent nine months of intense editing and proofreading share their impressions.

Senior Instructor Lee Seaman:

This is an amazing project. I began practicing Shintaido in Tokyo at the end of 1975. Ito-sensei had left for San Francisco the month before, the Shinjuku office was being run by Minagawa-sensei, and my first keikogi was labeled “Sogo-budo Renmei” rather than “Shintaido.” Because I understood Japanese, I was often asked to translate formally and informally at gasshukus, and we also went to Sunday services at Nogeyama, so I got to know many of the original Rakutenkai members. I’m so grateful for Pierre’s interviews, which capture the voices of their keiko and the joys, fears, and complex human relationships, not only of that time and place, but also the Shintaido art form as it lives and grows in our lives today.

Senior Instructor Lee Ordeman:

It was a privilege and a great benefit to participate as an editor for the Shakunetsu project. I helped edit the book’s biographical section, which will be of most interest to those of us who practice shintaido. Even though I practiced in Tokyo for 10 years in the 1990s, I only got to know a few of the Rakutenkai members mentioned in the book, and so I was very interested to finally read the personal stories of so many of our oldest sempai. I was fascinated to learn about their childhoods, sometimes very challenging, about how they met and started keiko with Aoki Sensei, Ito Sensei, and others, about their daily lives and experiences in keiko and what shintaido has meant to them beyond the dojo, even after leaving shintaido circles. All the bios inform our current practice and how we relate as a community. Some of them are quite moving and inspiring. I now enjoy a deeper sense of the people who came before me, whose bodies helped create and transmit the forms and the spirit of shintaido to others and ultimately to us. The movement of their bodies can be felt in our movement, and now their stories can be understood and felt as our story.

Senior Instructor Peter Furtado:

“I am a historian who has spent my career communicating academic historical understanding to non-academics and across cultures globally. Pierre asked me to help him in two key ways. First was to support his chapters that contextualize the interviews at the heart of the book, and in particular to work with him on placing the Rakutenkai in the context of 1960s Japan, notably its countercultural and radical spirit, in order to ensure that the book’s references, some of them quite obscure, make sense to a modern Anglophone audience. Second was to introduce the book by way of a Foreword that explains both its rather unusual structure and its author’s approach, deeply grounded in French academic tradition, in order to help the American reader, who is more likely to be a Shintaido practitioner than an anthropologist, understand what to expect.

It was a great privilege to contribute in this way and to work with Pierre who was amazingly constructive and responsive to queries great and small. I believe the book is both fascinating and important in multiple respects, and it’s wonderful that Shintaido of America has invested so much time and energy in publishing it in English.”

Instructor Nancy Billias:

Working on this project has been a very special kind of group kumite. Through proofreading and copyediting, I have learned so much about the origins and early days of Shintaido! What began as a chore became an enticing process. Each meeting has really been like a mini-keiko, with the instructors doing fine-tuned quality control in meticulous detail and with constant deep attention to faithfully transmitting the history of our art form. The result is a precious artifact that will benefit every Shintaido practitioner. Many thanks to Pierre and Ito and the whole team for their dedication to ensuring that these memories are recorded for future generations.

Gratitude is also given to other volunteers who gave their time and talents. These volunteers for editing include Stephen Billias, Derk Richardson,and Guy Bullen. Sarah Baker has formatted the work for a print-on-demand via Amazon. Thank you also goes to Mieko Hirano for consolidation of biographies and translation, Peter Furtado for the Preface of English edition, Pascal Lardellier for the French foreword and Jean-François Degremont for the afterword. Pierre Quettier receives the deepest gratitude for 20 years of nurturing the writing and translations of this book.

Want to learn more about the creation of this book? Watch these videos on the Shintaido of America YouTube Channel.

Do you have any questions? Contact us at info@shintaido.org

Purchase the book via Amazon

https://linktr.ee/shakunetsubook

Shakunetsu videos on the Shintaido of America YouTube Channel

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLVFMPkz9KuOclMue4Xaykxamq1yWH98TS

Project X

https://www.nhkint.or.jp/en/catalog/documentary/detail_industry_te/in_project-x.html

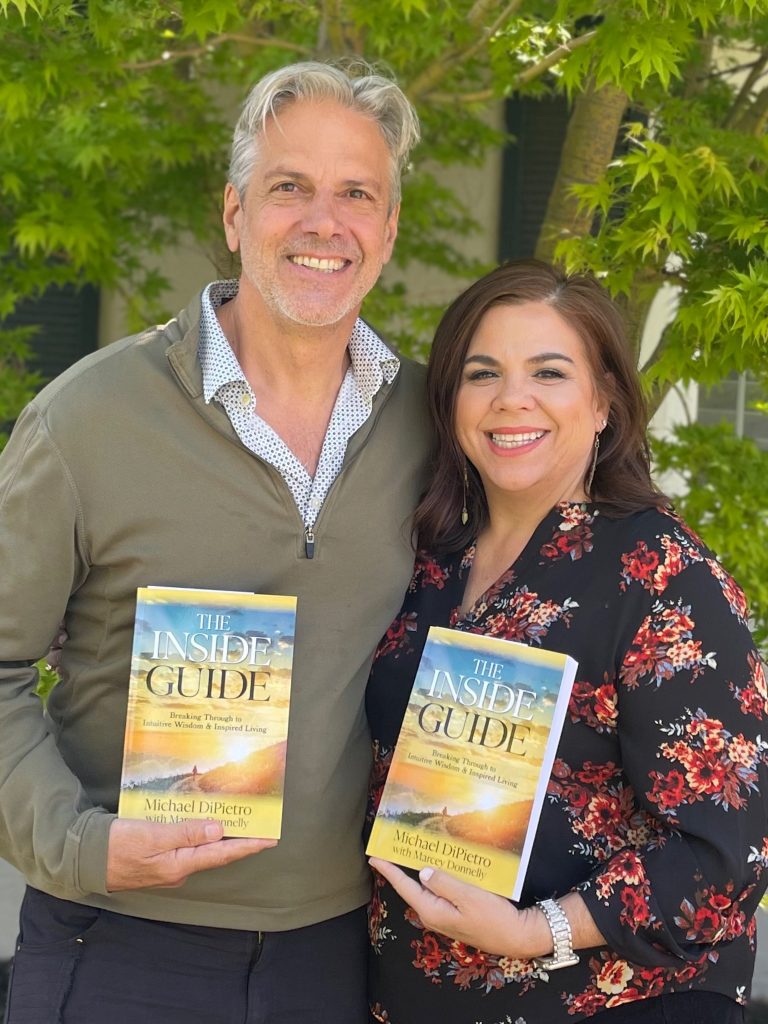

by Michael DiPietro

Much of the time when we undertake a new venture, we don’t know the full extent of what the journey will entail. Writing a book is a prime example of this. Recently, with the collaboration of my writing partner Marcey Donnelly, I self-published my debut book, “The Inside Guide: Breaking Through to Intuitive Wisdom and Inspired Living”. It has been quite a ride and I was honored when asked to share some of my experience in Shintaido’s “Body Dialogue.” This article aims to highlight the book’s overview, its connection to Shintaido, and how the practice helped me in preparation. Additionally, I will discuss specific aspects of Shintaido mentioned in the book and their significance.

A brief overview of the book

« The Inside Guide » serves as a transformative manual, guiding readers to introspection. Within its pages, a self-directed framework leads individuals on an inner journey, exploring their interior lives and uncovering innate wisdom. Offering breakthrough tools and profound insights, the book sheds light on how our minds create our reality. It empowers readers to work with their unconscious minds and unlock the hidden keys to lasting positive change. Moreover, it steers them toward a mystical awareness, culminating in living a truly inspired life aligned with their purpose.

The book is sectioned into three parts that are titled: Finding Answers, Overcoming Obstacles and Living Purpose. These parts also correlate to mind, body and spirit. Obviously, there is a link to Shintaido in these themes. I’ve always experienced Shintaido as a holistic practice, so even though much of the time the focus is on the body, our mind and spirit are developed as well. The book parallels a similar approach to keiko in reaching for the center of the being and then encouraging the reader to express their purpose from that center out into the world.

Why now for this book?

The timing of this books’ release is relevant as we consider the intersection of societal needs and the need for effective tools for the development of individuals.

In our current society, external distractions increasingly divert our attention away from introspection. Social media, daily demands, recreation, and even our focus on others often hinder us from dedicating time to self-reflection. Consequently, we are losing the contemplative focus crucial for personal growth. However, as most of us already know true transformation begins from within. The purpose of « The Inside Guide » is to inspire individuals to look inward and discover the peace, goodness, energy, and talents that lie within themselves.

In working with many clients over the years, I’ve seen a common theme that they cannot figure out how to clear what is holding them back. They keep getting stuck in the same recurring patterns that run interference on leading a full and happy life. By fostering greater awareness and equipping readers with practical tools, this book aims to enhance individual well-being for the betterment of society as a whole.

How Shintaido helped me prepare

Shintaido, with its holistic approach, played a significant role in my preparation for writing this book. Three particular practices come to mind:

Benefits of Shintaido in becoming more successful

Beyond the obvious health benefits of Shintaido, such as joint mobility, flexibility, strength and improved circulation, benefits also happen in the psycho-spiritual aspects. Body awareness helps us get in touch with unconscious content buried deep within, unveiling patterns that can limit our expression. We can use the practice to see how physical patterns in our body and in our movement reflect psychological patterns that can keep us inhibited. As we practice and become more fluid and natural in our movements, much of the time it will reflect and shift in the psychological pattern as well. Personally, Shintaido has helped me combat depression and discover a more vibrant and energized approach to daily life. By embracing the movement, the expression and the connection with others, I unlocked my natural abilities and found the confidence to be myself in a unique way. Shintaido practitioners find the practice when they are ready and gain the specific benefits they require at that point in their lives.

Some aspects of our practice that are mentioned directly in the book and why I included them in my work

The most obvious and explicit reference to Shintaido comes toward the end of the book when I talk about “proper timing in taking action.” I will share the excerpt below but I must first clarity why it positioned where I did and why I chose to include this particular practice. Throughout the book we work with the metaphor of reaching the mountaintop and returning to the village. This is a way of discussing our spiritual and/or peak experiences and the need for the integration of those experience into our everyday life. In part three of the book the focus is primarily on ways of being that support living an aware and awaked life in the world – the return to the village. To that ends, I chose to discuss proper timing as one of the ways people can work with living in the world. Here is what I wrote:

The Journey to the Mountaintop and the Return to the Village – pg 15

The mountaintop represents our retreat from everyday life and the clarity of enlightenment. We go to the mountaintop to have our spiritual experiences. The return to the village is the integration back into our everyday life of whatever spiritual experiences we have had on the mountaintop. That aspect, that return, is where a lot of people hit challenges.

We will discuss this more in Part Three, but it is important to understand that this book helps people make that journey back to the village. It gives them a roadmap not only for reaching their mountaintop, but just as importantly, for integrating their spiritual awakenings into their everyday life.

And then,

Proper Timing in Taking Action – pg 241

As we begin to follow spirit, listen internally, and take action in the world, there is a proper timing as to when to take action. We are looking for an opening or a window in time. What is the exact moment when my action is going to be most effective? Sometimes that means acting immediately; sometimes that means waiting. Not always jumping immediately into action, but waiting for the right timing. Waiting for some signal, the cue, or an opening.

How do you know the best moment to jump into action?

It is almost like a window opens and then you jump through it! If you wait for the proper timing, then when you take action, it works like magic, like clockwork. If the timing isn’t right, things may not work out.

This concept comes from martial arts. In the martial art I practiced called Shintaido, when we are practicing “attack and receive” scenarios, there is a proper timing to receiving your opponent’s attack. If your timing is superb, you can move in a relaxed, slow state and still beat the other person. We call that “A-timing.” If I am too soon, my opponent has time to adapt. If my timing is too late, then I must speed up and rush to deal with the situation. There is a timing that comes from perceiving the right moment but in a different kind of way. The perception, how to sense into that, is a different kind of perception.

When we practiced, we explored that timing by learning to sense the other person’s intent in our own bodies. When anyone moves their body in any way, there is first an intent in the mind. Then that intent travels in their nervous system, to their muscles, until it transfers into movement. When you get sensitive and open enough, you can actually feel another person’s intent. Before they actually start to move, you can move according to their intent. This means you are already ahead of them once they actually start the movement.

By analogy, we can see that there is a proper timing to our actions. If you are too soon or too late on your timing, you are not going to have the most effective outcome. This may seem like a very nebulous concept. Even during martial arts practice, it was very nebulous. It is almost like a “psychic feeling” in your body; this person is about to move, and I act, trusting my body’s sense. If they’re already moving, I am too late.

What is this little window of proper timing? When is the moment when your action is going to be most effective? If it is too soon or too late, you might not have the best results.

You can begin to track it by noticing your timing in everyday life. Are you showing up right on time? Are you showing up early? Are you running late? If you say, “Oh, I am running late,” your timing is not correct. If you are too early to your appointments, then it is also not proper timing.

Being “on time” is being in the right place at the right time. Notice if you are showing up early or late in your life and explore adjusting your timing. Maybe something is saying, “Not yet.” Maybe wait a day or two, a week or two. We are just trying to listen for those “impressions,” if you will. The gut hunch on when is best.

All of Part Two of the book is primarily focused on the body, but more specifically on our neurology and how it affects our experience. However, toward the beginning of Part Two, we discuss the importance of the body and increasing one’s sensitivities by noticing more subtly in the body. This seems to have a particularly Shintaido “feel” to it, so I will share these excerpts:

Your Body Allows You to Feel – pg 111

If you did not have your body, you would not have the ability to have experiences. More specifically, your body is exceedingly important for the feeling aspect of your experiences. Your feelings are a very important piece in the field of transformation as well as for your inner guidance. Noticing feelings is an ability that comes easier for some and takes practice for others.

The deeper truth of your experiences comes from the somatic or body level. An experience from the somatic level will often show you more than you could uncover through a verbal inquiry from a mental place. It can show you more quickly and more efficiently if you’re willing to see it.

You can begin to explore sensations and your different experiences from a somatic perspective by asking yourself, for example, “Where am I feeling this sensation? What does it feel like in my gut? What do my hips feel like?”

You could go piece by piece through your body and begin to notice experiences at the body level. When there is a particular experience there is a way to start exploring.

Exercise

Sit still. Keep your spine straight.

Then notice.

What sensations come up? What do you do with those?

Accept them by allowing them to be.

These are the first two levels in working with a somatic approach

in transformation. Notice the sensation and allow it.

Sometimes this exercise will begin to unlock some of the emotions that go along with an experience. If you sit quietly long enough and do not try to “wiggle out” of something, generally, the deeper content starts to arise.

Sometimes you can be carrying emotions in your body and you do not notice it until you sit in silence. You may start to recognize a particular feeling or that something was going on that you were not in touch with. That is part of meditation; that is part of noticing.

However, there are instances when noticing and accepting does not get to the desired change in a deeper pattern. In those cases, we need to practice transformation, and that is what this part of the book is about, the deeper keys to transforming your experiences.

For now, this is about noticing the feelings in your body. Recognizing feelings pulls you out of your mind because you actually notice what is happening in your body. It bears repeating: If you did not have your body, you would not have the ability to have experiences. Through this practice of noticing you create an opening for more information. Exploring through your body is the key. Again, your body is very important.

Deeper Aspects of Your Body – pg 112

Since the body is what allows you to have experiences, you can begin to build your ability to notice your sensations with finer and finer levels of detail. You might have a sensation, but there are the gross and the subtle levels of the sensations you encounter. Typically, people only notice what is coarse or heavier, but as you progress, you build your acuity to notice the sensations with more and more granularity.

As things get deeper, as you progress more into the spiritual aspects, or the unknown dimensions of the inner terrain, a lot of times very subtle sensations can have a very big impact. Generally, when the sensations are subtle, they are more difficult to notice. In addition to the awareness of the sensation, as we have mentioned, the location in your body of the various sensations is also a big factor in developing your acuity.

What are you feeling for a certain experience in your body and where are you feeling it?

The body holds certain aspects from many of the experiences in our past. We hold things in our hips, we hold things in our backs, we hold things in our shoulders, and so on. As you start to explore through the body, you can notice where you are holding tension. What happens as you begin to work with that tension? What content thoughts, feelings, memories or emotions arise as you release certain tensions in your body? This tension is sometimes referred to as our “body armoring.” It is a way people protect themselves from the unconscious content they don’t want to see.

Throughout the book we also highlight key concepts and then, for easy reference, we provide a summary of all these key concepts at the end of each part. The following example is from the excerpt above and is the main takeaway that bears repeating:

KEY CONCEPT

Without our bodies we would not have experiences. Through the practice of noticing how our bodies respond to the external world, we create a new level of understanding ourselves.

There are various other small instances throughout the book that a Shintaido practitioner could identify as inspired by the practice. I have given these few examples in the hopes that you better understand the link of Shintaido practice to the success of whatever endeavors you undertake in your life. It has been a great honor to share my perspectives with you and I invite you to read the entire book and explore working with me directly if you want to accelerate your transformative journey. Many Blessings!

Michael DiPietro

Transformational Guide, Master of Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP), Shintaido Instructor

Email: michael@loveguide.us

Website: www.loveguides.us

For following on social media use: www.linktr.ee/insideguide

The Inside Guide available on Amazon: click here