Shintaido in The Time of Covid : Across Space and Time

By Sandra Bengtsson

Listening to a program on the radio about a vaccine for Covid 19, I heard the following statement: “We can’t use the outdated techniques of January 2020 to develop this vaccine”. January, 2020, outdated – really! But if we look at life now compared to then it’s an understatement.

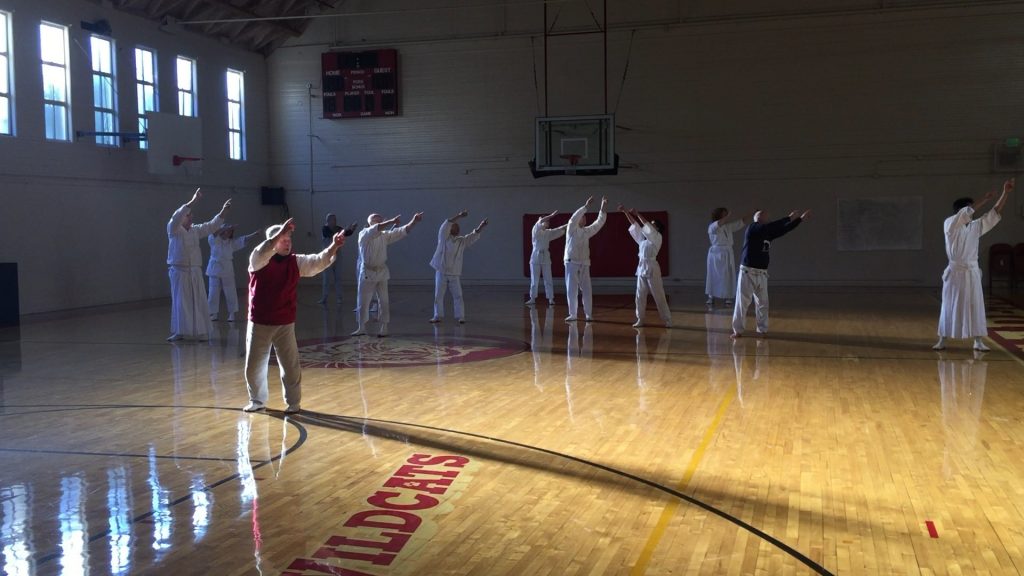

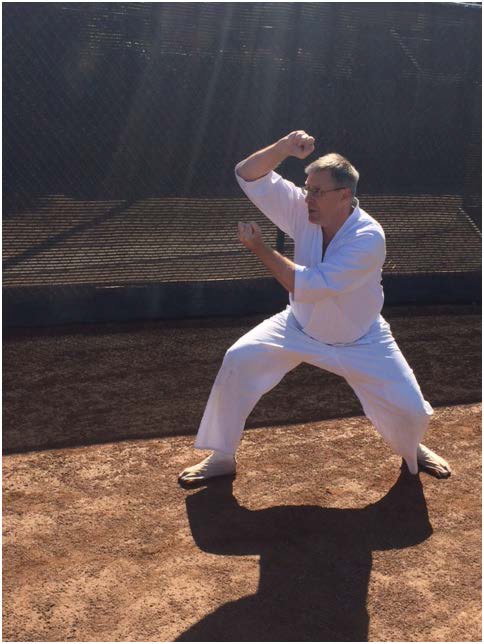

The last Shintaido class I attended in person was on March 8th at our usual Sunday at Marin Academy, just north of San Francisco. This was our regular weekly class that Robert Gaston, Connie Borden and I have co-taught for several years. Curriculum varies, but we had been focusing on Shintaido Kenjutsu and Jissen-Kumitachi. Per usual, after keiko we went to eat, and amid the bustle of brunch talked about the virus and what we knew. Connie, as a medical professional, gave us an update on viruses in general and we all discussed our thoughts, feelings, and concerns.

On March 16th, the Bay Area was placed under a Shelter in Place order. My husband and daughter Rob & Sally Gaston and I shared our very cozy home for the next 10 weeks, leaving only to buy groceries or take walks.

Rob had been participating in Pierre’s Taimyo remote keiko but since that was in the middle of my office workday, I hadn’t. At home I could and I did. It was a lifesaver. While I was never drawn to Taimyo – this approach, in this time, was perfect. A little before 2pm an alarm would go off on Rob’s phone – it was like a call to prayer. I set aside my work and settled myself into Taimyo.

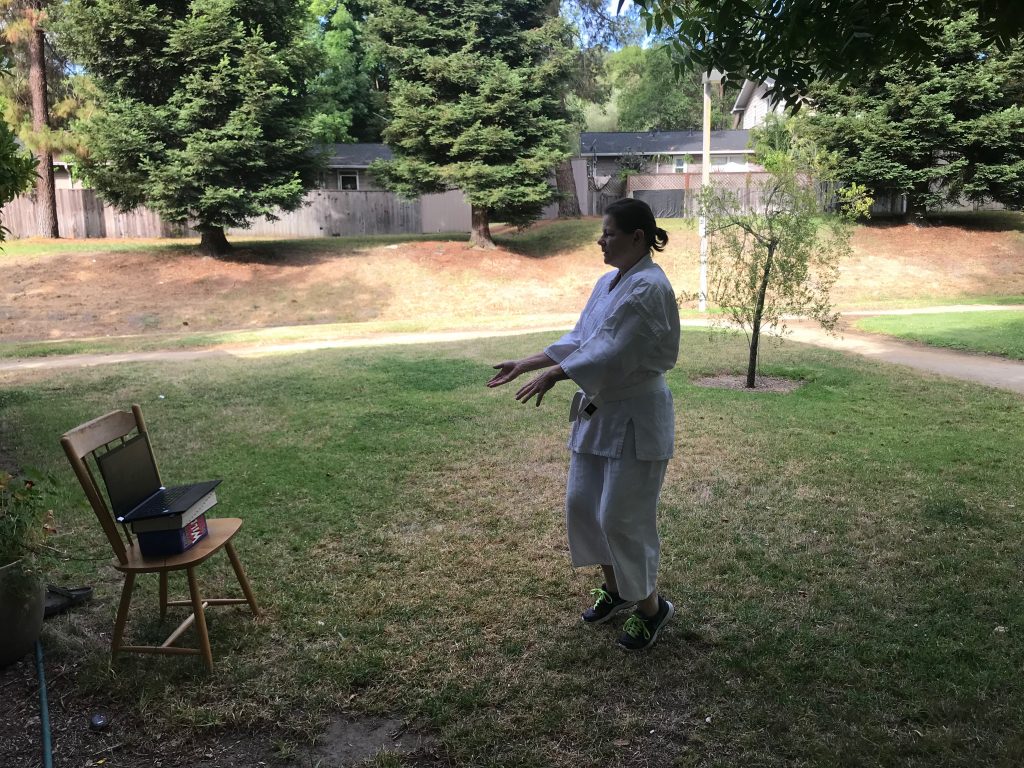

We began teaching Sunday class on April 5th via Zoom. Keiko is 45 minutes: Warm-ups, Kata (Taimyo/Tensho/Diamond Eight) and a brief conversation afterwards. It’s been a comfortable time to re-connect, practice familiar movements and keep our weekly Shintaido schedule active.

Around May 1st, Connie mentioned to me that there was going to be a British Shintaido Online Daienshu June 7th-21st. The format was Sunday keiko with Minagawa and Gianni, during the week personal Taimyo kata and several keiko in small groups, each led by an instructor. As my first international event was a British Shintaido Daienshu in 1989, I thought why not?

As I do prior to every event, I began my plan to reduce my involvement in the gasshuku. I had limited expectations about Zoom keiko; the keiko times were earlier than advertised; I couldn’t practice during the week because I was back to work—all variations on my usual pre-gasshuku angst. In fact, I said to Jim Sterling prior to this event, “if Gianni teaches stepping, I’m going to ask for a refund!”

The first Sunday keiko came and it was really something. Minagawa & Gianni taught as they always had: warm-ups, tachi jumps, eiko dai, tenso, shoko, daijodan kirioroshi, taikimai and azora taiso, finishing with self-care. Some movement was open hand, some with bokuto.

They weren’t teaching as they always had, but what was happening was gasshuku keiko. The teaching method was familiar: sensei demonstrate, sensei and students perform the movement one time together, and then students practice individually while sensei encouraged, corrected and supported.

Afterwards was the discussion: heart-felt, a bit too long, with extensive “thank yous” and clapping. A real post- gasshuku discussion!

Next came Sunday 6/14. Again, many of the elements of the first keiko, progressing to stepping practice and then to expansive movement. And no, I didn’t want a refund. It was amazing! In a very small space Gianni taught hangetsu stepping practice, tenshingoso dai, tsuki to many levels, leading to tsuki moving freely. In my small living room, I was transported.

And for the last keiko, Minagawa began the keiko with Diamond Eight movement. Then as Gianni taught the balance of the class, he presented (a new to me) sword kihon using portions Diamond Eight movements. I was so excited to be offered new movements to practice and learn!

After class, we had a final discussion, complete with a group photo – “the more things change, the more they stay the same.”

To assess these approaches, I look at both the teacher and student perspectives. Most importantly from the Daienshu, it was extremely successful because the sensei did not limit themselves when presenting the classes through Zoom. This was critical. As a student, I had a more positive and enriching experience when I concentrated on receiving the teaching as it was presented, and did not focus on how it was different from gorei I had received before. In both cases, the Zoom filter was removed. Just when I forgot about “Beginner’s Mind” it came to the forefront again.

My thoughts on these approaches to keiko:

Taimyo

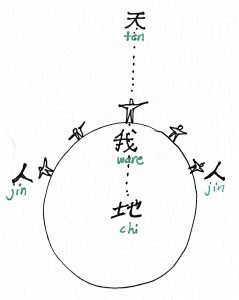

Practicing a specific movement at a specific time with others across the world reminded me of the power of Shintaido. We know how to move through space and time; this ability enhanced this practice. I could feel others practicing and they felt the same. Pierre’s gorei directed me and connected me to Taimyo.

Narrative gorei: Students listen and move as verbally instructed by sensei: “reach to front as in “E” then when reaching eye level , open to “O” and then exhaling circle back low then front softly, “O” not too high”

Sunday class

Visual and audio gorei: Students watch and follow, with verbal & physical presentation of the movement by sensei.

SGB Daienshu

Again, what really worked about the Daienshu was that the teachers did not allow themselves to be limited by Zoom. Neither Minagawa or Gianni referred to it except for minor technical reasons. It allowed us to connect, but did not limit the connection. Also, was clear that a great amount of time and thought was spent creating a cohesive, expansive and integrated program.

As we continue with virtual keiko we will develop and fine-tune these styles. I have gone from being pretty down-hearted to quite enthusiastic about the possibilities. Gorei as a thread that lifts and carries us is being re-defined.

Aoki-sensei quotes from the code of Master Koizumi on page 61 of the Shintaido text book:

“Martial arts must change with the demands of each age, otherwise they are of no use to the warrior.”

YouTube Link – Sunday Zoom Keiko with Sandra, Rob Gaston and Connie Borden