by Pamela Olton

One day this spring, I was wandering around the desktop of my Mac, clearing out old files, trashing grade documents from classes I will never teach again. But the mouse arrow kept skating over a pile of “screen shots.” As I was pulled into the pile, a wonderful image popped up of a celestial Chinese calligraphy or brush stroke painting that I kept from ten years before, when I attended a neurology class in our Doctoral program at ACTCM.

What I remembered more was a companion handout which included a smaller black and white version from a PowerPoint slide labeled “MOTOR EXAM” with the six basic beginning steps of learning to do a neuro exam. I was deeply interested in the medical subject and all of Dr. Hao’s years of experience and skill using scalp needles to improve many difficult cases.

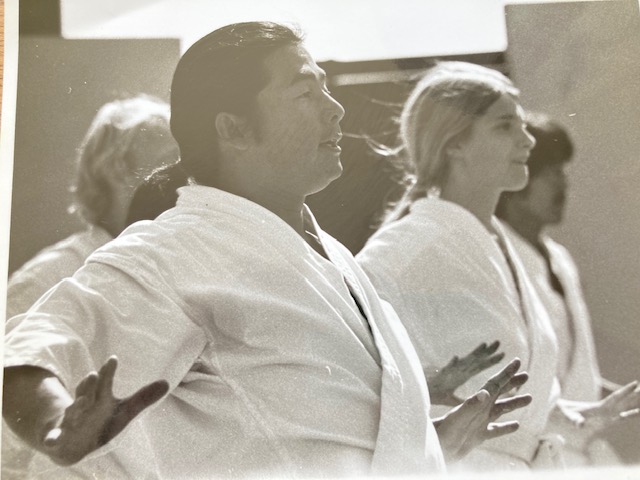

But alone, the beauty of the painting was stunning, especially since I was back on Sundays enjoying Taimyo, on Zoom. Each hour of these classes has reminded me of the richness of Shintaido and has helped my (nearly) 75-year-old body wake up and reengage in the movements, the company and the more ethereal stuff: Qi, composure, and the “oneness with nature and the group.”

I got a wake-up call, and continue to feel this each week, about how much lack of balance has become part of my being. I have been going through medical treatments since last fall that may continue for the rest of my life. I have been diagnosed with Hemochromatosis, too much iron in my blood and organs, something that goes undiagnosed often until we are too old to do anything about it. But that aside, my body is giving me new lessons and Shintaido is a great ally helping me to stop at least some of my dizzy spells.

I enjoyed reading Sally Gaston’s article about her relationship to Shintaido over the years. I wish I had been that young when beginning to train in Shintaido. But what I thought about those younger days, is that even at 25 when I began Shintaido, I didn’t need to think about balance. In fact, when I was a small child in Long Island, we ran up and down hills, high bluffs of sand and rocky piles at the waterfronts where with or with our shoes we would chase each other on wet rocks and never fall down.

At first, my relationship with Shintaido was to build up muscle and strength without competition as in other “sports” as well as learning to be still, quiet and willing to learn a new world of culture, community, trust and inner strength: that was the real new deal.

The balance I see in Dr. Hao’s painting is meticulous brushwork. As an acupuncturist, I have been looking at it now, not as Motor Exam diagram, but more like the revelation of the secret interiors of the human body that has treasures beyond Western medical anatomy, or what modern medicine knows and can see with technical machines and blood tests. It shows the millennium or two of study and meditation that built Chinese medicine’s understanding of diagnosis and treatment. The balance of treating the exterior using massage, needles etc. with the understanding the deeper interior systems that we now learn in acupuncture school.

There are major meridians that we see on the maps and there are the Eight Extra meridians, each working together to balance the Qi of the body which holds up the strength and health of the exterior. Even for those of us who have not studied medicine, eastern or western, when I ponder the loveliness of the calligraphy, I think of Shintaido in several ways: I think of the various Kata we learn and practice, I think of our Wakame movements, and I think of the idea of Ten/ Chi/Jin. I think of balance in movement and balance in stillness and quiet.

Thank you Pam. Great Article.

Hey Pamela.. i assume the calligraphy is by Aoki?