“Shintaido: The body is a message of the universe” written by Hiroyuki Aoki

A Shintaido of American Podcast Series.

Watch/Rewatch the Release Party on YouTube.

This Shintaido of America podcast series was produced by a group of volunteers. Technical support funding was generously provided through the Joe Zawielski Memorial Fund and Shintaido of America membership dues.

If you are not already a member, please consider a Shintaido of America membership today, or help support us by making a tax-deductible donation to this 501(c)(3) organization.

EPISODES

Episode 1 : Episode 2 : Episode 3 : Episode 4 : Episode 5

Episode 6 : Episode 7 : Episode 8 : Episode 9 : Episode 10

Episode 11 : Episode 12 : Episode 13 : Episode 14

Episode 1: “The atom bomb inspires an avant-garde martial art”

Section of the Book:

About the Author and Book by Shintaido of America

Introduction by Michael Thompson

Translator’s Note by H.F. Ito

Life, Burn by Hiroyuki Aoki

Episode 1 introduces us to Hiroyuki Aoki, the founder of Shintaido. Master Shintaido instructors Michael Thompson and H.F. Ito offer their perspectives, while the last essay was written by the young Mr. Aoki before Shintaido was established.

Read more about Episode 1

Hiroyuki Aoki, the founder of Shintaido, has been called a “pioneer,” and the discipline he created with the Rakutenkai group in the 1960s has been called “an avant-garde martial art.” As children, Aoki and members of the group experienced the bombing of Japan during World War Two, and many lost family members to the atomic bomb. But even as the technology of war continued to increase its destructive power, these young people dove deep into the traditional fighting techniques of Japanese martial arts to transform the essence of these ancient teachings into a movement discipline for modern society.

As one of Aoki’s students, Michael Thompson, writes: “Shintaido contains elements of the martial arts which appear violent and meditation which is quite calm and peaceful. They are not any more mutually exclusive than the two hemispheres of our brain.”

Another of Aoki’s students, Haruyoshi Ito, writes: “The more violence is turned into a form of spiritual garbage through misunderstanding and suppression, the more virulent is its odor when the cap blows off and it is finally released…”

Mr Aoki’s aim in founding the Rakutenkai group was to seek creative solutions to the psychological, interpersonal, and ecological challenges of violence. Along the way, they invented an amazing system of training for both body and mind that can benefit everyone, regardless of age, gender, or physical condition.

This is the story of the body movement discipline they created in answer to the challenges of modernity: Shintaido, the “new body way.”

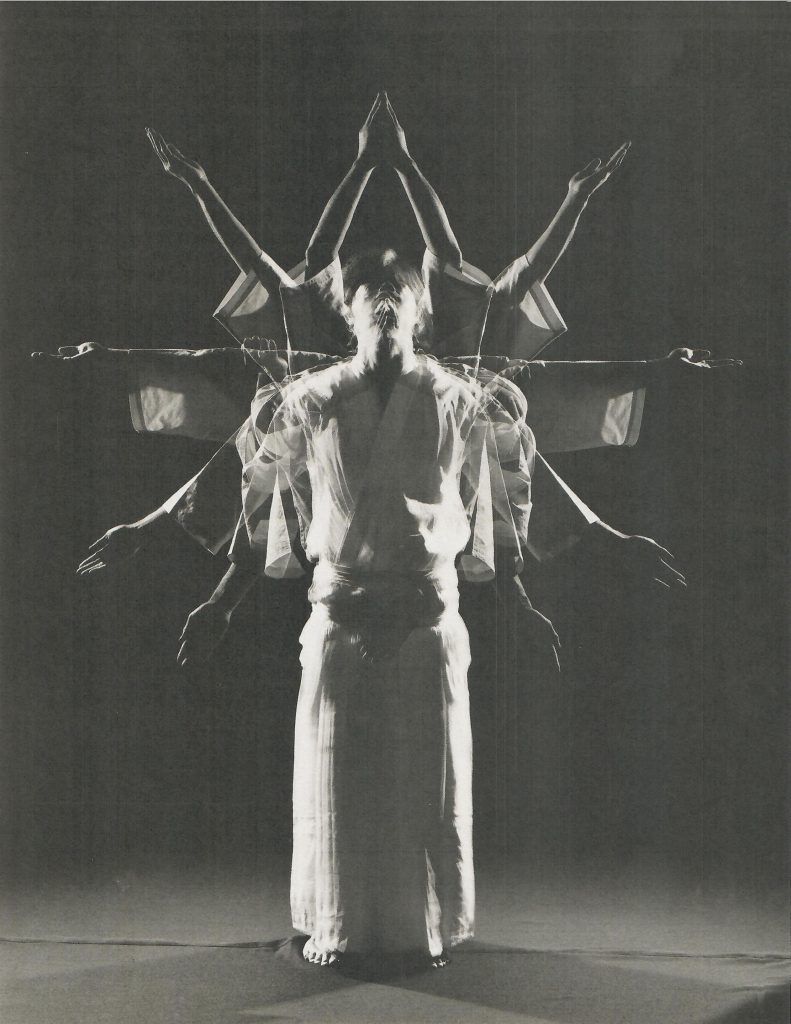

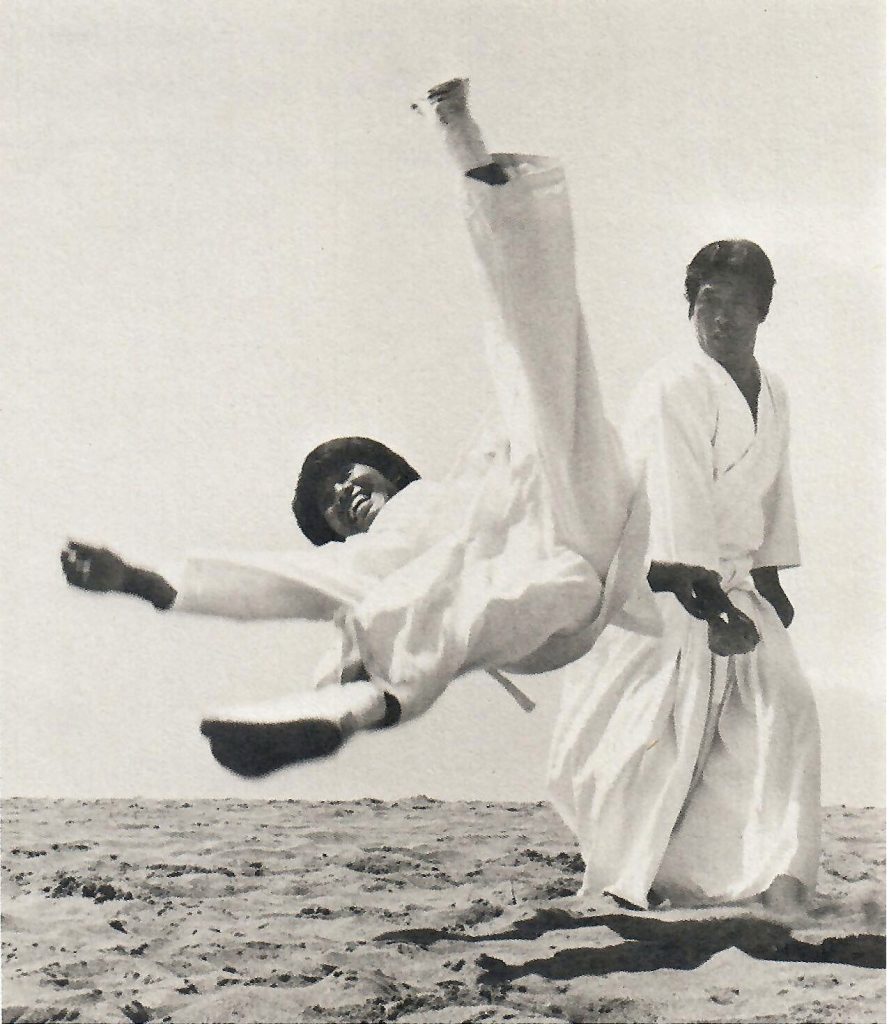

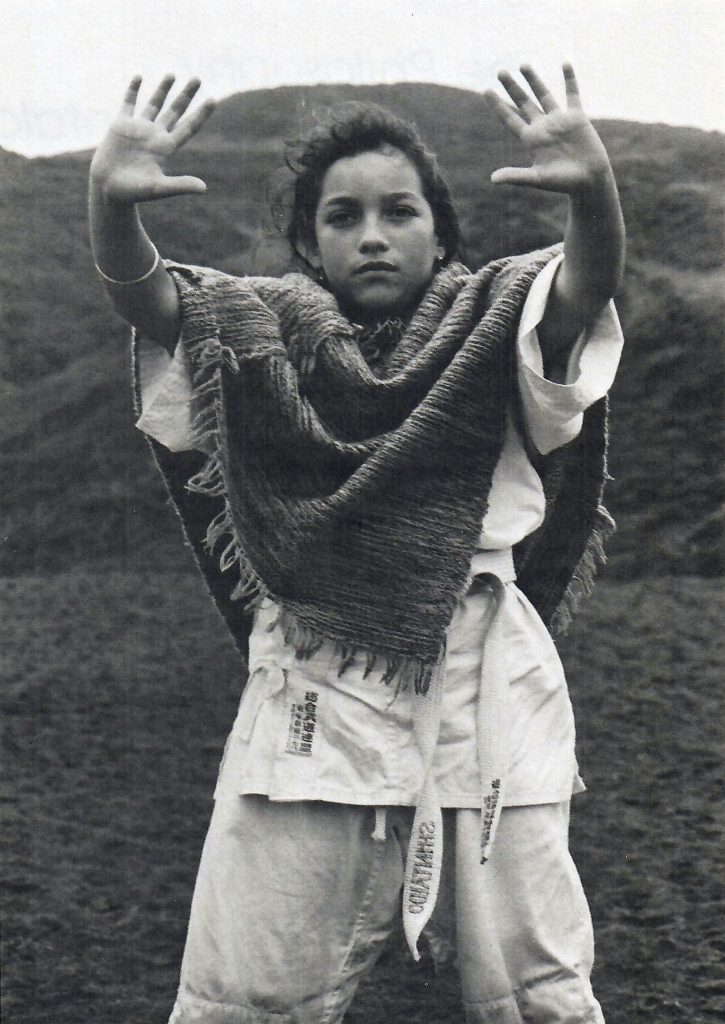

Images from the book

Top of Page

Episode 2: “What is Shintaido?”

Section of the Book:

Part 1: The Philosophy and History of Shintaido

– Chapter 1: What is Shintaido?

In Episode 2, Aoki describes the basic character of Shintaido as a system of body movement that can be a guide to solving problems within ourselves, in our relationships with others, and even in our relationship to the cosmos, the source of our lives.

Read more about Episode 2

“As a mood or feeling, Shintaido is more religious and artistic than scientific. It is more emotional and primitive than rational,” writes Shintaido’s founder, Hiroyuki Aoki. “It involves cooperation more than competition in its movements. But it is cooperation that emphasizes individual expression, rather than passive group enjoyment.… Shintaido cannot be understood by trying to pigeon-hole it into traditional or popular categories such as martial arts, gymnastics, health fads, or religion.”

The difficulty of creating an art that overcomes barriers to mutual understanding is something Aoki understands well. Shintaido grows from the soil of Japan’s ancient traditions, but it is not necessary to “turn Japanese” to master it. A child of the 1960s, Shintaido speaks to an international audience and invites everyone to experience movement that is not “…constrained by tense shoulders, …[and] clenched fists, but rather one in which our hands and bodies are open to our partner and our neighbor in a gesture of respect, forgiveness and acceptance.” Thinking about body movement this way, it is easier to see how Shintaido, although born from the masters of the samurai tradition, may be closer in spirit to master artists such as Gauguin or William Blake.

Images from the book

Top of Page

Episode 3: “Meeting karate master Egami-sensei”

Section of the Book:

Part 1: The Philosophy and History of Shintaido

– Chapter 2: How Shintaido was born

– Introduction to Chapter 2

– Section 1: Meeting Master Shigeru Egami

Read more about Episode 3

Before Shintaido was created decades ago, its founder, Hiroyuki Aoki, was a young student of drama and visual art. It was only by accident — when his acting teacher suggested that he should study karate to improve his acting skills — that he met karate master Shigeru Egami. Aoki’s artistic approach to body movement gave impetus to the discipline that eventually became Shintaido.

“As a lover of music and art, I also wanted Shintaido to have the same value as the works of Bach or Mozart in music, or as the works of Michelangelo, Cezanne or Picasso in the world of art, or as the great works of literature.… The philosophy of these artists in the modern period is as familiar to most Japanese as boiled rice and miso soup.”

Egami’s approach to karate was already far from traditional. Aoki writes that according to Egami “…the practice of karate involves competition within oneself. … He completely changed the traditional and feudalistic conception of our practice.… Through his teaching, karate movement suddenly approached the basic thinking of the artists and philosophers I had always admired…” And yet, his artistic drive led the young Aoki to feel confused: having become the highest-ranking black belt under his teacher, he was on the certain pathway of an apprentice, poised to take over master Egami’s Shotokai karate school. But the pathway of an artist demands constant exploration and often impels one to pursue the unexpected and the uncertain.

Top of Page

Episode 4: “How is a karate master like a symphonic conductor?”

Section of the Book:

Part 1: The Philosophy and History of Shintaido

– Chapter 2: How Shintaido was born

– Section 2: Gorei as conducting and classical studies through kata

Read more about Episode 4

Imagine that you are watching a group of dancers, or martial artists, moving in synchronization, the group naturally breathing as one, timing synchronized to the microsecond, but not with military rigidity — they are moving with the naturalness and grace a school of fish or a flock of birds. The scene shifts to a classical orchestra, each section and each musician contributing a part, which the conductor weaves together into a spectacular whole.

Part of Aoki’s inspiration in Shintaido was gained through the perspiration as master Egami’s disciple, leading karate training in his school. The choreographer, the orchestral conductor, and the karate master all share something in common: the ability to “orchestrate” group activity, to give “gorei” (号令). Aoki describes his experience leading classes in the Shotokai karate training hall: “Once I started to lead the whole class using a gorei, I was never allowed to break my concentration even for a second.”

In Shintaido, the aim of the leader has shifted away from preparing the participants for combat, and has moved much closer to that of the choreographer or conductor: letting the individual talent of each person shine, while contributing positively to the life of the whole. Under Egami’s direction, Aoki also immersed himself in the classical kata of karate, researching and documenting them in detail. But his goals lay beyond the preservation of a great tradition. “The difficult task of collecting these karate kata continued,” writes Aoki, “as well as my study of other body movements. Eventually, this all blossomed into Tenshingoso (the Five Cosmic Breaths), …which became the first basic technique (or kata) of Shintaido.”

Top of Page

Episode 5: “The martial arts and the evolution of consciousness”

Section of the Book:

Part 1: The Philosophy and History of Shintaido

– Chapter 2: How Shintaido was born

– Section 3: the martial arts and the history of the evolution of consciousness

Read more about Episode 5

Although Shintaido is a “new” body way, it exists on the foundation of an ancient samurai warrior tradition. But when guns were appeared on the battlefields of Japan in the 16th century, it changed the calculus. Imagine fighters who had trained for years integrating movement, mental focus, and breathing to attain an advantage on the battlefield— killed en masse in short time by a less-trained but better-equipped army, their training and armor suddenly tactically useless against this new weapon.

From the introduction of guns in mediaeval Japan and onward, technological developments in warfare branched off in one direction, leading to the atomic bomb and other advances in military hardware, a trend which continues to this day.

The musket by itself did not cause the elite samurai warriors to become interested in meditation, calligraphy, landscape painting, tea ceremony, and other art forms. But it did make clear that in the modern age, military victories are achieved largely by technological superiority. Meanwhile, the spiritual aspect of the warrior’s “combat” grew into the samurai philosophy of living perfectly up to the moment of death. In a sense, the atomic bomb in 1945 may have revealed a similar truth as rifles did in the 16th century: if the goal is simply winning, technology is decisive. But the ancient martial arts include a kind of “technology” of movement that works with the mind and body and connects us to nature. Much of this traditional body “technology” (or rather, systematic set of training techniques) has little to do with battles, fighting, winning and losing. These teachings are the starting point of Shintaido.

Top of Page

Episode 6: “An ancient sword master expands space-time”

Section of the Book:

Part 1: The Philosophy and History of Shintaido

– Chapter 2: How Shintaido was born

– Section 4: The sword technique of Hariyaga Sekiun: expanding time, space, and energy

Read more about Episode 6

Imagine two samurai warriors of nearly-even status and skill, facing each other on a narrow bridge in the mountains, both wanting to cross, and both honor-bound not to back down. In a few moments, one of them will be dead, and neither knows if it will be him or his opponent. At this moment when everything becomes silent just before the battle, both are striving to sense even the smallest hint of the impulse to move, the slightest sound of the weight shifting in anticipation of an attack. They are intensely “tuned-in” to each other. Each one’s knows that his survival may depend on his capacity for mindfulness. The slightest gap in attention might mean instant death.

At this moment, we might say that these “opponents” are in a sense “unified.” This was the insight of the mediaeval swordsman Hariyaga Sekiun, and his insight was tested in practice multiple times. Sekiun’s philosophy was influenced by Zen, and his teaching aimed to strip away occult practices and pre-conceived responses to an attack. Therefore Aoki considers Sekiun to be in the same category as avant-garde artists of the modern era, who changed our way of seeing. He clarifies the relevance of a thinker like Sekiun: “…[E]ven though the present time is far different than the classic age of martial arts, it offers many new directions and adversaries which must be confronted. We have the responsibility and obligation to express our opinions and beliefs to our nation and our leaders, especially in regard to social and environmental problems. Our movement, therefore, must be different from what has come before.”

Top of Page

Episode 7: “Putting the art back into the martial arts”

Section of the Book:

Part 1: The Philosophy and History of Shintaido

– Chapter 2: How Shintaido was born

– Section 5: developing a modern martial art

Read more about Episode 7

If ancient movement arts—if we widen our focus beyond martial arts to include, for example, traditional Japanese Noh theater or tea ceremony—if these ways of movement are not just “museum pieces” but are still relevant for us today as contemporary, living systems of physical training; then we might ask if they should be not just revived or preserved, but somehow re-invented. Aoki explains his goals in the process of inventing Shintaido, as he writes:

“By using body movement, we could regain a measure of the genuine communication which has almost disappeared from our lives, and at the same time, repair our bodies and minds from the damaging effects of modern civilization.…

“After retracing the last three hundred years of martial arts history, I concluded that just as modern art had to be created in its own historical context, the martial arts could be adapted to modern conditions, and the forms and movements would be completely different from the traditional styles.

“…[T]he simple study of classical methods never produces a new way of expression. One cannot be an Andy Warhol merely by practicing drawing for a prescribed amount of time. Similarly, I did not limit my study to karate and the other martial arts in this limited way.” The purpose of Shintaido, as Aoki summarizes it, is “…not to preserve old classical forms and transmit them to succeeding generations,” but to use “…a body movement or the martial arts to examine the conditions of our own age.”

Top of Page

Episode 8: “The locus of one swing of the sword is a sign”

Section of the Book:

Part 1: The Philosophy and History of Shintaido

– Chapter 2: How Shintaido was born

– Section 6: the locus described by the swing of the sword is itself a sign— stripping away spirituality

Read more about Episode 8

“What is cutting?”– this question, which seems simple, reminds us of a koan, the genre of seemingly nonsensical questions or proverbs used as teaching occasions in Zen. Generally there are no verbal koans in Shintaido, because it is above all a body movement discipline. But might there be such a thing as a physical koan, a quest or a question “asked” in the language of movement? Aoki’s answer to the question “What is cutting?” is mysterious: “The locus of the swing of the sword is itself a sign,” which suggests that the answer is yes.

Aoki reveals the process by which he arrived at this formulation, which grew from an urge to strip away everything that he perceived as unnecessary, to eliminate any artificial elements or superficial “spiritual” meanings, leaving only the essential, primordial aspects of the movements to shine through. He describes his approach: “I tried to remove all spiritual gloss until we could reach a ‘zero point’ … Finally the day came when the meaning of all techniques became zero for me…” From this description, we might get a glimpse of the process by which Shintaido was invented, we might even say the “paradigm shift” that happened for Aoki in the quest to invent Shintaido.

Top of Page

Episode 9: “Discovering the world of true natural body movement”

Section of the Book:

Part 1: The Philosophy and History of Shintaido

– Chapter 2: How Shintaido was born

– Section 7: Looking for the strongest technique

Read more about Episode 9

What do a cobbler, an infant, and a Buddhist statue have in common? This may sound at first like the set-up for a joke, or simply an absurd question. But in fact, here Aoki describes how his search for principles of truly natural movement led beyond the formulaic prescriptions common in many traditional martial arts. “Even though babies have had no physical training, their expression of power is so strong and automatic that it is difficult for us to imitate,” he writes. Paradoxically, he sees a similarity in the movements of master craftsmen (who of course are highly trained): “On close inspection, I discovered that as an artisan works, his seemingly slow movements are soft and devoid of shoulder tension.” Integrating these observations with the study of the postures and hand gestures of ancient Buddhist statues led Aoki to the signature gesture of Shintaido called “kai sho ken,” the wide-open hand with palm and fingers completely stretched and extended. Aoki describes this discovery: “I finally found that the open hand… was stronger than the hardest fist because when we open our hands, we can automatically express the full power of our life energy.” In combination with other hand positions such as a tight fist or a completely relaxed hand, the open hand becomes one of the fundamentals of the holistic training system that was soon to be named “Shintaido.”

Top of Page

Episode 10: “Giving voice to the hidden cosmic breath”

Section of the Book:

Part 1: The Philosophy and History of Shintaido

– Chapter 2: How Shintaido was born

– Section 8: Tenshingoso— an embodiment of the hidden cosmic breath

Read more about Episode 10

Episode 10 describes the creation of the foundational kata (a sequence of movements) of Shintaido, which in the title of this section Aoki calls “an embodiment of the hidden cosmic breath.” In Aoki’s mind, this kata, like a great work of art, should be “…an embodiment and expression of the common Tao of many different disciplines, [which] simulates the cycle of a human life and even the rhythm of the cosmos.” He also intended that the kata should be concise and simple, take only a few minutes to practice, be accessible to wide range of people, require little space, help us focus on the infinite horizon, support a bright, well-rounded character, and function as an antidote to the routine discouragements of daily life. The sequence of movements, usually accompanied by the vocalizations, that emerged after a thorough process of testing and refinement was named Tenshingoso, the Five Breaths of Cosmic Reality.

Aoki acknowledges that he achieved these ambitious aims by “standing on the shoulders of giants,” as Isaac Newton said, and expresses his gratitude to his former teacher Shigeru Egami of Shotokai karate-do, and to master Hoken Inoue (also called Noriako Inoue) and his art of Shinwa Taido (also called Shin’ei Taido). Inoue was the nephew of Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of Aikido. In many traditional martial arts, such a kata, a nugget of essential knowledge of the discipline, would be kept as a secret, known only to the select few. But Aoki’s aim was different than that of traditional martial arts, and so Tenshingoso — the Five Breaths of Cosmic Reality — was made a central pillar of Shintaido, and anyone who practices may start learning it during the first lesson.

Top of Page

Episode 11: “Scream to the sky: the gyroscope of Shintaido”

Section of the Book:

Part 1: The Philosophy and History of Shintaido

– Chapter 2: How Shintaido was born

– Section 9: The birth of Eiko — the gyroscope of Shintaido

Read more about Episode 11

Imagine that you are being invited to join a series of trainings or practices that are described like this:

People joining this training have to put their house in order before each practice, as if they might not return. Our purpose is to discover our physical limits and the threshold of the unknown world which begins at the end of our psychological strength.

These were the conditions for the people who invented Shintaido, the Rakutenkai group, which was formed under Hiroyuki Aoki’s leadership in 1965. In the last episode, we heard about Tenshingoso, the five breaths of cosmic reality. This episode presents the other fundamental form of Shintaido: Eiko no ken, the “sword of glory,” known now simply as Eiko or “glory,” which Aoki describes as the “gyroscope” of Shintaido.

Top of Page

Episode 12: “Playing with light”

Section of the Book:

Part 1: The Philosophy and History of Shintaido

– Chapter 3: What Shintaido has conceived: Hikari to tawamureru — “playing with light”

Read more about Episode 12

Imagine that in creating Shintaido, expert martial artists were asked to commit themselves fully to a partner exercise — in Japanese “kumite” — that was nothing like “sparring,” that was completely outside the norms and standard practices of any traditional martial art. Aoki describes Hikari to Tawamureru, meaning “playing with light” like this: “All that is required is that we express ourselves as simply and sincerely as possible, regardless of our physical strength. It is not even necessary to move. It is enough simply to play or just be present. This kumite is a revival of the childhood expression that we lost by growing up

Top of Page

Episode 13: ”To overcome the barriers to mutual understanding”

Section of the Book:

Part 1: The Philosophy and History of Shintaido

– Chapter 4: To overcome the barriers to mutual understanding

Read more about Episode 13

Teaching and learning — sharing knowledge as opposed to mere information — is a profound process that changes the lives of the individuals involved. The types of social relationships that exist in Japan — Shintaido’s country of origin — are different than those in the USA or Europe. Logically, this has a powerful impact on how we understand the teaching and learning process. In this episode of the podcast, Aoki shares his insights into this question from the perspective of an author of an entire body of knowledge — a body of knowledge that grew from Japanese soil, but has taken root in the USA, Canada, Australia, Europe, and elsewhere outside Japan.

Top of Page

Episode 14: “How to make this age better”

Section of the Book:

Part 1: The Philosophy and History of Shintaido

– Chapter 5: How to make this age better

Read more about Episode 14

“Creativity is not the exclusive province of artists and artistic expression. If we stop the automatic acts of daily life, surrendering yesterday’s happenings and separating ourselves from the old self of one day ago, through an act of our will, we will discover a new life of continuing satori, or many small enlightenments…” With these words, Aoki succinctly brings home the relationship between the physical movement practice of Shintaido and its meaning in the broader context of so-called ‘spiritual’ traditions, and most importantly, describes its immediate application to our daily lives.