Rediscovering Kyukajo: Pacific Shintaido Kangeiko 2020

By Derk Richardson

When Pacific Shintaido invited Master Instructor H.F. Ito to be the special guest instructor for the PacShin Kangeiko 2020, it was with a poignant sense of historical import. We knew, given Ito sensei’s plans to cut back on international travel from his home in France, that this was likely to be one of his last formal workshops in the San Francisco Bay Area.

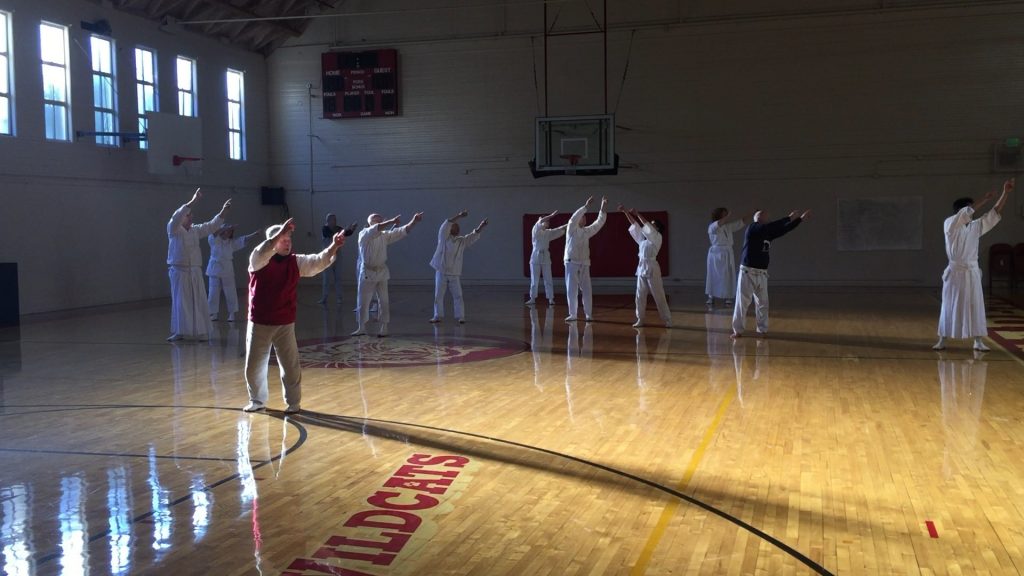

From a position of deep respect, the PacShin board—Shin Aoki, Cheryl Williams, and Derk Richardson—requested that Ito sensei define the curriculum theme for the two-day gasshuku, which was held at Marin Academy, San Rafael, on the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday weekend, Saturday and Sunday, January 18–19, 2020, with an additional workshop for advanced practitioners on Monday, January 20. Master Ito chose “Rediscovering Kyukajo.” His intention, he explained, was to share what he described as his “new appreciation” of the series of nine-plus techniques fundamental to classic Shintaido Kenjutsu practice.

Asked to deliver remarks at the Sunday afternoon closing ceremony, Master Ito, true to his unpredictable nature, chose to deliver them during Saturday morning’s opening ceremony. He kept them brief. He eschewed long, nostalgic reminiscences, and quoted General Douglas MacArthur’s 1951 farewell speech to Congress: “Old soldiers never die; they just fade away.”

But Master Ito did offer slightly lengthier introductory remarks to set a conceptual tone for the gasshuku. He showed us three styles of kanji representing the idea ten (“heaven” /天)—the precise, formal, stroke-by-stroke kaisho calligraphy; the more flowing, semi-cursive gyosho approach; and the free-flowing sosho style. By “Rediscovering Kyukajo,” Ito sensei meant returning to—and finding new meaning in—the fundamental kaisho movements of Kyukajo. Many Shintaido kenjutsu practitioners have practiced Jissen-Kumitachi for so long that the flow of continuous kumite in a wakame-informed sosho style has become second nature. Ito sensei took us back to the original nature of Kyukajo as a way of reinvigorating and deepening our practice.

Over the course of three keiko—Saturday morning, Saturday afternoon, and Sunday Afternoon—Master Ito led a dozen or so practitioners of mixed age and experience through the 14 Kyukajo techniques. Although kyu indicates that there are nine techniques, numbers three (sankajo), four (yonkajo), five (gokajo), eight (hachikajo), and nine (kyukajo) each have a basic and an advanced movement. During the general keiko on Saturday and Sunday, Master Ito taught ikkajo (one) through nanakajo (seven) and jumped over hachikajo (eight) to kyukajo (nine). He held over the more complex hachikajo for the Advanced Workshop on Monday. With different kumite partners during the three keiko, we repeated and refined our footwork and sword movements, and experienced how timing and ma are unique to different partner pairings.

In addition to guiding us in rediscovering Kyukajo, Master Ito shared his renewed understanding of three elements that are basic to formal Kyukajo practice: It should be done with the straight sword, bokuto, designed by the founder of Shintaido, Master Aoki Sensei, rather than bokken; stepping sequences all end by drawing the feet into musubidachi stance; and each kumite begins with partners bowing to each other, drawing their swords into shoko position, lifting their swords in tandem into tenso, and returning together down to shoko. The partners repeat shoko-tenso and bow at the conclusion of kumitachi, as well.

Beyond Kyukajo. On Sunday morning, with Robert Gaston serving as exam coordinator, Connie Borden as goreisha, and Ito sensei as examiner, Nicole Masters took her exam—and was the next day awarded her certificate—for Shintaido Kenjutsu Shodan. In the gap between the exam and the break for midday brunch, while Ito sensei and National Technical Council members retreated for exam evaluation, Lee Ordeman, visiting from Washington D.C., taught a fun and brisk mini keiko focused primarily on stepping practice. Between-keiko potluck brunches were hosted by Sandra Bengtsson and Robert Gaston (Saturday) and Jim and Toni Galli Sterling (Sunday). Michael Sheets was the videographer for the gasshuku and documented every step of Ito sensei’s teaching—both for posterity and for the eventual production of edited segments for study.

At the conclusion of the general Kangeiko on Sunday, PacShin presented Ito sensei with two gifts in gratitude for his teaching and invaluable contributions to the cultivation of Shintaido in the Bay Area over the past forty-six years—a beautiful bokuto/bokken cover stitched from upcycled fabrics by Nao Kobayashi, and a hard-bound book of historical photographs and written tributes from Shintaido practitioners who benefited from Master Ito’s teaching in the Bay Area. The true gifts, however, have moved in the other direction: They are the knowledge, wisdom, and practices, all of which carry over into everyday life, which Master Ito has bestowed on us all.