by Stephen Billias As an aging Shintaido practitioner, I find the meditative aspects of Shintaido: Taimyo, Ten-Position Meditation, Diamond Eight, Kenkain Hoko (Flower Walking) appeal to my body more than…

Read moreShintaido, Past, Present and Future

This is a publication of British Shintaido. It was the first inaugural lecture, given by Peter Furtado in January 2021, about the Rakuntenkai group who developed Shintaido with Aoki Sensei in the 1960s, and the importance of their mission to the world today.

Read moreShintaido Kenjutsu Q & A with Master H.F.Ito.

Interview by Sarah Baker – January 2020

What is Shintaido Kenjutsu? Shintaido means “New Body Way,” or we could also call it a new art movement of life expression. When people hear Shintaido, the syllable at the end is Do, which is usually used for martial arts. But Shintaido is more than a martial art. It is a movement for the development of human potential.

What is the difference between Kendo and Kenjutsu (Judo and Jujutsu)? Kenjutsu means sword-fighting techniques. So Shintaido Kenjutsu presents your life expression through sword techniques. During the samurai period in Japan, no one used the word kendo (or judo, for that matter). The terms were kenjutsu and jujutsu, and they referred to fighting techniques. The words kendo and judo came into use as Japan began to modernize, after the Meiji Restoration around 1865. That marked the end of the samurai fighting lifestyle. People were no longer allowed to take matters like law and order, and revenge into their own hands; those things were now handled by the police and the courts. Sword techniques and other martial arts were still practiced, but more as a form of sports or physical training, and done in spaces akin to a gymnasium. That’s when the terms kendo and judo came into popular use.

Kendo literally means “the way of the sword,” and Judo literally means “the way of flexibility.” Although those words sound great, and the practice is supposed to lead to enlightenment, that kind of keiko can actually become hollow and inflexible when it is removed from the demands of the battlefield. At its core, Shintaido is designed to help us experience life-and-death interactions without actually having to kill each other.

What is the difference between Karate and Kenjutsu from your cultural point of view? Karate came from Okinawa and as a result there was a great deal of influence from Chinese martial arts because Okinawa was occupied by China and Japan and various times in history. Kenjutsu is totally Japanese, and is affected by what we call the “island culture” of Japan, meaning that it was relatively isolated and not much influenced by other martial art forms. In addition, Kenjutsu has close ties to Zen, which is the form of Buddhism that was followed by many Japanese samurai.

Karate characteristically has kata, practiced individually, kihon, practiced in unison with a group, and kumite, practiced with a partner. Traditionally in Kenjutsu, both Kihon & Kata werepracticed individually, not in unison.

Because Karate has group exercises, Master Aoki was able to develop Goreijutsu, techniques for giving gorei. This is one of the strong points of Karate, from its Chinese influence.

Karate is a horizontal relationship: it’s very practical. The instructors are not responsible for their students’ spiritual development. Kenjutsu has a big vertical component – mind-body-spirit – and the instructor works to develop all of those in his or her students.

Where does Kyu-Ka-Jo Kumitachi come from? In Shintaido: A New Art of Movement and Life Expression (1982), Master Aoki said that Kyu-Ka-Jo Kumitachi came from Master Inoue Hoken, who was the founder of Shinwa Taido. I heard a rumor that Master Inoue was in the line of Itto Ryu Kenjutsu, and Master Ueshiba was in the line of Shinkage Ryu Kenjutsu. I believe that Kyu-Ka-Jo Kumitachi came from the Itto Ryu tradition. That means Shintaido practitioners are so fortunate, because we have access through our keiko to the traditional Itto Ryu practice.

What is Jissen Kumitachi? The original concept of Jissen Kumitachi came from a project team consisting of Master Okada, Master Minagawa, and me. Kyu-Ka-Jo Kumitachi is a great vehicle for spiritual development and mind- body harmony, but it isn’t necessarily very practical in terms of working sword technique. By that time, I had studied Shin Kendo from Master Obata in Los Angeles, and because of his Aikido background, he had a lot of Shinkage Ryu influence. So the three of us were able to benefit from the strong points of Shinkage Ryu in our work with Jissen Kumitachi. The word jissen can be written two different ways in Japanese: 実戦 and 実践. The pronunciation is the same, but the first one means “for practical fighting” and the second one means “for practical living.” We were able to incorporate the mixed wisdom of both Shinkage Ryu and Itto Ryu into Jissen Kumitachi.

What is the difference between Bokuto and Bokken? In the regular martial arts world, bokuto 木刀 and bokken 木剣 are the same. Both mean “wooden sword.” But in Shintaido, we make a distinction: the bokuto is a straight wooden sword and the bokken is curved. We recommend that you use a bokuto when you practice Kyu-Ka-Jo Kumitachi, and that you use a bokken for Jissen Kumitachi.

More specifically, the original, formal bokuto practice was designed by Master Aoki. He believes that the bokuto form can naturally help practitioners experience Ten-Chi-Jin vertical energy when doing Tenso. Shintaido Kenjutsu (e.g. Kyu-Ka-Jo Kumitachi) is meant to be practiced with a bokuto (straight wooden sword).

Shintaido Kenjutsu (e.g. Jissen Kumitachi) is meant to be practiced with bokken (curved wooden sword). And in both cases, it is very important to study and experience the techniques and philosophy of Tenso and Shoko when you are a Shintaido beginner.

What is the difference between Kirikomi and Kiriharai

See Hiroyuki Aoki, Shintaido: A New Art of Movement and Life Expression (1982) – , pages 46-47 and 70-73.

2 Shintaido Kenjutsu Q&A with Master H.F. Ito

What is Toitsu Kihon? See Hiroyuki Aoki, Shintaido: A New Art of Movement and Life Expression (1982) – pages 88-99.

What is the relationship between Master Egami, Master Inoue, Master Funakoshi, Master Aoki? See Tomi Nagai-Rothe’s scroll of our inheritance from three masters, created in the 1990s.

What is your overview of Shintaido history as a stream of consciousness? Shotokai Karate ~ Egami-Karate ~ Rakutenkai-Karate ~ Discovery of Kaisho-Ken ~ Shintaido (Toitsu-kihon) ~ Discovery of Tenshingoso & Eiko ~ Sogo-Budo ~ Shintaido-Bojutsu/Karate ~ Yoki-Kei Shintaido ~ Shintaido as a human potential movement

What is Shintaido Kenjutsu for you? My life work, the conclusion of my life time training of Shintaido, a crystal/reflection of Kaiho-Kei Shintaido, Yoki-Kei Shintaido, Shintaido Bojutsu, and Shintaido Karate.

What is your recommendation to those who want to start studying Shintaido Kenjutsu? If you are a beginner, you should study Shintaido Daikihon first: specifically, Tenshingoso, Eiko, and Hikari/Wakame (Stage 1). After that, Toitsu Kumite using kaishoken (Stage 2). Then you can start Kyukajo Kumitachi (Stage 3), and after that Jissen Kumitachi (Stage 4).

If you already have experience with another martial art, especially related to Kenjutsu, you can jump in at Jissen Kumitachi (Stage 4), and if you like it, you can then study Kyukajo Kumitachi, too. And if you really want to understand the discipline in depth, you’ll end up studying the Daikihon (Stages 1 and 2), too.

Appendix

Have you studied any other martial art besides Shintaido ?

I’ve never joined or belonged to any other martial arts dojo, but I did six months of training at the Aikido Headquarters in Japan in 1970. That was just after Master Aoki had completed the Daikihon, and right after Master Ueshiba had passed away. Master Aoki was ready to come out of the “Egami World,” and he sent me to the Aikido Headquarters to see how practical what he had taught me really was, and to see what Master Ueshiba’s legacy was − his secret key points. (In Japanese, we say, “Find out what is written on his tombstone”). Master Aoki didn’t tell me how long I would be there, so I assumed it might be for a year or more. Every night I would come home, and he’d ask me what I had studied. I got more and more interested in Aikido, and I was surrounded by people who had studied with Master Ueshiba, even though I had never met him myself. But, I was really flexible because of all my hard keiko at that time, so their joint locks didn’t work on me (I didn’t tell them, of course, I was respectful), and my tsuki was really strong, so I knew I could hit them any time (but I didn’t do it of course, I was respectful). I was working with an older man, not an instructor, and I was attacking him gently, but once I attacked him strongly without warning, and suddenly I ended up on the floor! After that, I became much more respectful toward Aikido. When I told Master Aoki that story he said, “Okay, you don’t need to go there anymore.” I think Master Aoki was collecting Aikido techniques through me, but he probably recognized that I had been getting rather proud of myself, so he likely sent me to the Aikido dojo to learn some humility, and respect toward other martial arts.

Soon after I was appointed as Doshu (Master Instructor) in 1988 in Tanzawa, Japan. Master Aoki said that since I was a Master Instructor, I needed to go and study Tameshigiri (actual cutting techniques) from Master Toshishiro Obata. He had been the Tameshigiri champion in Japan for five years before he moved to Los Angeles around 1985.

Master Obata was still new to the US when I first met him in 1989. He was one of the top disciples of Gozo Shioda who was 10th Dan in Aikido. (I think he studied directly from Master Ueshiba.) He was the founder of Yoshinkan Aikido a school of Aikido that is famous for being extremely practical and very difficult.

Starting in 1989, I studied with Master Obata three or four times a year, about a week at a time, for three years. I thought I was there to learn test cutting, but I ended up also practicing Yoshinkan Aikido and Kenjutsu. At that point he called his style Toyama-Ryu Battojutsu, which was the kind of training that was taught to Japanese Army officers during wartime. Very practical – scary practical, actually ! In Los Angeles, Master Obata had a small Aikido dojo, but his teaching was so demanding that he was not very successful with his dojo. When I first started to study with him, he didn’t speak English very well, and was very frustrated with his American students. He complained, “They have no guts, no manners, and no concentration !” Of course, I know how to study from Japanese masters, so he shared a lot with me. It was like a brain dump – all of his frustration, but all of his technical skills in Aikido and Kenjutsu, too. He taught me a lot, but he was very tough on me – I would be black and blue all over after working with him for a week. He would whack me with his practice stick whenever I left an opening. We were practicing kata, and from his perspective he wasn’t hitting me – he was teaching me. But he couldn’t treat his American students like that because they would sue him. And Master Aoki had introduced me to him as a 20-year practitioner and his best student. So, he was very generous, but also very challenging. And, of course, this wasn’t kendo with a lot of armor – we didn’t have any kind of protection. I guess I had become proud again ! So, this was a good lesson, too.

Interview by Sarah Baker. Sarah was born in the Bahamas (1965) to American parents. She returned to Rhode Island in 1966 and moved to Massachusetts in 1969. She has been a caregiver and Touch Pro Certified Practitioner since 2003. She holds Aikido 2-dan examined by Don Cardoza (Aikido 5-dan) founder and head instructor of the Wellness Resource Center, North Dartmouth, MA. in 2011. She holds Shintaido Kenjutsu 1-dan examined by H. F. Ito at the Doshokai Workshop, September 2019. Presently she resides in Sarasota, Florida. She acts as the project manager, Shintaido of Americavideo documentation archive project

H.F. Ito’s Bay Area Summer Workshop 2019

By Derk Richardson and Connie Borden

On Saturday, August 17, at Marin Academy in San Rafael, California, Master Instructor H.F. Ito led Bay Area and visiting Shintaido practitioners—12 in the morning session, 10 in the afternoon—through two keiko based on the theme “Opening the Door of Perception: Muso-Ken.” Given his intention to cut back on transatlantic travel from his home in France and to visit North America only once a year, this was possibly Ito Sensei’s last summer workshop in Northern California. For some of us, that fact added a subtly poignant undertone to Ito Sensei’s deep and nuanced teaching. Throughout the day, Sarah Baker and John Bevis documented the workshop on video.

Keiko began with a form of warm-ups that was new to many of us. Connie Borden introduced the movements based on the end of Taimyo kata part III flowing into the start of Taimyo part I.

These movements are called Hugging the Sky (ho-ten-kokyu-ho), Three Quarters turn (hokushin kokyu-ho), oodachi zanshin, and kan ki. They focused on breathing (kokyu) while having us rotating, spiraling, and twisting our spine and our being to reach higher into the heavens and lower into the center of earth. We studied contrasts of creating a small circle below ourselves then opening diagonally to draw a big circle and embrace the sky. As we bowed, we studied compressing the air and space in front of us. To start hokushin kokyu-ho, we hugged a tree in front of us and then slowly expanded ourselves upward and downward, experiencing the contrast between up and down while elongating our beings, continuing our focus on deep and slow breathing. Our front hand reached up with the fingers and palm facing back, while the lower hand pointed down and three-quarters behind ourselves with the palm facing inwards.

Throughout these movements we practiced having our eyes follow our movements, ultimately having our eye movement help us go further into space and across time. In the last segment, we opened to Ten with kaisho-ken hands to the sky and then formed a tight tsuki to grasp what was waiting for us, then crossing our arms in front of ourselves we ended in the classic karate stance, kaiho-tai. With kan ki as the opening of Taimyo part I, we reached out in front of ourselves as if to dive out into the ocean of ki, and after making one last big circle around ourselves, we let ki energy land in our outstretched, wide-open palms and made a tight tsuki. We pulled our tsuki back to our sides, letting our elbows point behind ourselves while deepening into kiba-dachi (horse-riding stance). After holding this stance for a moment to allow our bodies to feel warmed, we stood in seiritsu-tai, letting our arms move downwards to our sides with our fingers actively pointed downwards. From the warmups of breathing, twisting, spiraling, and elongating, we ended feeling straight and clear, hopefully ready to study awareness of ourselves and increase understanding of others.

Before we began physical practice, we sat in a circle and Ito Sensei gave a free-flowing talk based on a double-sided handout. With Tomi Nagai-Rothe and Nao Kobayashi assisting with translation, he first discussed the various forms of ki (energy or, in French, esprit), ranging from lack of confidence/fearfulness (yowa-ki) to being resolute and ready (tsuyo-ki) or easy going (non-ki), from taking care of your own energy (ki wo tutete) to being considerate of and attentive to others (ki-kubari), and more.

The thorny concept of sak-ki, which translated to “bloodthirstiness” or “the intention to kill,” was pivotal because it related closely to the second area of discussion, muso-ken. In our practice, we would be working on developing sensitivity to energy behind us, specifically the intention and approach of someone attacking us from behind. Mu-so, Ito Sensei explained, can be taken to mean “dream,” “vision,” “premonition,” and “clairvoyance,” on the one hand, or “no phase,” “no phenomenon,” and “emptiness,” on the other, akin to the complete absence of light or dark matter.

Muso-ken, then, can be thought of as employing the sword of perception, the English definition given by French Shintaido General Instructor Pierre Quettier. And the physical practice of the morning and afternoon was dedicated to learning how to use this sword effectively.

We began with partner wakame, the initiator using a lighter and lighter touch at a quickening pace, and the receiver developing a more and more refined sensitivity to the contact and the direction of the energy through the body. Ito Sensei emphasized that wakame is something that you can never assume to have perfected, something to work on for the rest of your life—in relationships, in the family, at work, and out in the world.

The core of the practice was developing sensitivity with our backs, making our entire backside a sensor (or an array of sensors), like radar, detecting and becoming aware of what’s coming at us from behind. As we cultivated sensitivity to someone approaching from behind, we worked on two different stepping patterns to receive the attack. One involved stepping forward and slightly out (with the right foot, for instance), opening a path for the attacker by pivoting and drawing the left foot slightly aside and “welcoming” her to enter and pass with a Tenshingoso “E” motion with the left hand. The second stepping pattern involved stepping back and slightly behind (with the right foot, for instance), again opening a path by pivoting that leaves room, but not too much, for the attacker to pass, and again welcoming and urging the partner forward with a right-hand “E” motion. Both techniques are ways of managing space and time. Although Ito Sensei did not talk much about it, receivers were encouraged to be aware of and experiment with A, B, and C timing on the early-to-late-response spectrum.

After working on the stepping, the receivers took up weapons—a rolled magazine playing the part of a short stick, and then either a boken or bokuto—and added gedan bari and ha-so movements to their receiving.

As for the attackers, they approached their receiving kumite partners from behind with different techniques (and weapons), as well: using the first movements of the Diamond Eight Cut kata and stepping forward with a spearing motion; using a rolled up magazine as a short stick; and using a boken or bokuto. During the afternoon keiko, Ito Sensei had us receive dai jodan sword attacks from behind, eventually receiving two attackers so that we could gauge and deal with their different energies. Between sessions, we retreated to the home of Jim and Toni Sterling for a potluck brunch that became a continuation of keiko through social communion and philosophical discussion.

Toward the end of the afternoon keiko, Ito Sensei talked a bit about Tenshingoso in metaphorical terms, likening the patterned movements to a constant turning inside out, as we might do with socks; extending ourselves to the other side of the earth and beyond the boundaries of the universe; holding our planet with loving kindness and bringing it inside ourselves. Finally, he charged us with solo “homework” practice of the Muso-Ken movements he had taught us, and reminded us that we need to apply our Shintaido practice in general to the way we think about life and death, and the way we live our lives in the world.

Shintaido Presentation at 2nd Global Conference on Death, Dying and the 21st Century

by

Connie Borden-Sheets

On April 13, 2019 in Bruges, Belgium, I presented Shintaido for a second year at the 2nd Global Conference on Death, Dying and the 21st Century. This year 22 people from 10 countries came together for 2 days as an interdisciplinary research community. We discussed the ways culture impacts the care for the dying, the overall experience of dying, and the ways the dead are remembered. Attendees came from the Netherlands, Australia, Portugal, Switzerland, Wales, the UK, Israel, Lebanon, the USA, and Canada. Our interdisciplinary group included scholars from philosophy, ethics, the law and literature; experts in the field of design for both products and processes; photography and videography; writers; and healthcare professionals including me as both a healthcare professional and student of Shintaido.

I presented Tenshingoso with overtone chanting, as part of an array of topics from personal reflection on the journey through and after death of a loved one to review of literature and poems that gave voice to the illness experience. During the 45-minute interactive demonstration, the participants used their voices and their bodies to explore the sounds of Ah, Oh and Um to express grief and facilitate mourning. Participants were first given the opportunity to stand facing inwards in a circle, and then with alternating groups they were invited to stand in the center of the group while these three movements were being done by the external circle.

Group Movement in Bruges

Our group quickly formed an intimacy and connection through our mutual sharing and teaching over these two days. For almost everyone, these two days moving toward the unknown and mystery of death brought us closer together. I received feedback that the inclusion of body movement was welcome to both “get out of our heads and into our bodies” and to facilitate our interconnection as a group. I am making plans for next year’s meeting already!

Bruges canal

Here is my paper on my presentation:

Kotodama Applications for End of Life; a performance/audience participation presentation

Abstract: The use of sound combined with body movement crosses all cultures, languages and religions to provide a physical means for spiritual growth that for end-of-life purposes can provide a way to express grief and connection with the deceased. When the voice is added in Japanese martial arts such as Shintaido, the sound can be a spiritual basis for teaching. The Japanese word for sacred sound or word spirit is Kotodama. In the Japanese belief system, mystical powers dwell in words or names and ritual word usages can influence our environment. The Japanese martial arts body movement is Tenshingoso, with specific attention to the sounds “Ooo”, “Uumm”, and “Aaa”. This presentation will bring the results many years of weekly practice and instruction for use in celebrations of life.

Presentation: Tenshingoso is called “The Cycle of Life” so that through body movement one can study life as measured from moments to a lifetime, while using the voice to increase the flow of energy. Tenshingoso is derived from esoteric Buddhism with each movement accompanied by a Sanskrit sound. For this presentation, the sounds of O-Um-Ah will be presented and practiced. This movement with voice will advance to transition from one sound to the next sound ultimately doing three sounds with one breath.

O – Reaching out into the universe to reach what is omnipresent

Push hands forward and up as far as possible with the palm facing forward, fingers pulled back so as to open the palm of the hand. The sound of “Oooo” is made throughout this movement and as the movement Um is started, the sound changes to “Uumm” to start the stage of Um.

Um – Bringing the universe, perhaps those who have gone before into one’s center

The right-hand rests lightly inside your left hand. Eyes can be half closed or completely closed. Bring all your concentration into one single point where everything else disappears. Release all tension from the top of your head to your feet. Bring the hands back to rest lightly over your lower abdomen. The sound of “Uumm”” continues through this movement and begins to change to the sound “Aahh” to start the stage of Ah.

Ah – Opening Space – asking those who have died to reappear.

Opening your eyes, drop your arms down and backwards with shoulders relaxed, your fingers open and palms open, leading with the thumbs pointing backwards. Look toward the skies. Your chest will be open, head tilted backwards so that your chin and face is looking up. Your arms with palms open will be at your sides. Making the sound of “Aahh” and transitioning to the sound “Ooo”.

Shintaido in Transition

by

Michael Thompson

Recently I came upon a reference to Howard Schultz, who founded the Starbucks chain. It described the transition of the company from “founder-led” to “founder-inspired” now that he has retired from day-to-day involvement. This is a good way to describe the current state of affairs in the Shintaido universe. Aoki-sensei has retired from active involvement in the international Shintaido movement and is focusing on his work in the Japanese Tenshinkai school as well as participating in the international Le Ciel Foundation project. We have moved to a “founder-inspired” phase of our history.

Aoki-sensei’s last creative endeavor has been the founding of a Kenbu school in Japan and Europe. A bilingual Japanese/English text has been published. Several YouTube videos have been posted for anyone who might be interested in that development.

Aoki-sensei Kenbu

The current international organization (ISP/ITEC), under the direction of Ito-sensei and Minagawa-sensei, is working to develop a third pillar of the Shintaido curriculum–Kenjutsu–to go along with Shintaido Karate and Bojutsu. So far there has been no cross-pollination between the two sword practices, although we shouldn’t rule it out in the future once the international kenjutsu task force has completed its work.

During this transitional phase I would like to see the Shintaido curriculum move from the martial arts/dan examination model to an instructor certification system. Rather than having a separate assistant category, there could be a combined advanced student/assistant evaluation which would precede the first examination, now called Graduate. This ranking in turn would be replaced by an instructor certification designation, recognition that an individual is qualified to teach Shintaido. The Senior Instructor level would be open to someone who has a teaching resume as well as a demonstrated advanced keiko level, roughly encompassing the curriculum now in effect. The entire bokuto Kyukajo program should be completed by then.

General Instructor would become an honorary title conferred by the international organization in recognition of long-term commitment and contribution to the practice and dissemination of Shintaido. The title of “Doshu” should be retired with the current holders for now, perhaps to be resuscitated in the future if deemed appropriate.

The Japanese martial arts kyu/dan examination/ranking system would still be used in the three pillars of Shintaido Karate, Bojutsu, and Kenjutsu. It’s time to reframe Shintaido itself as a separate art which was Aoki-sensei’s original idea and inspiration.

Pacific Shintaido Kangeiko 2019

By Shin Aoki and Derk Richardson

Over the Martin Luther King, Jr. weekend, January 19–21, Pacific Shintaido hosted its Kangeiko 2019 at Marin Academy in San Rafael, California. Master Instructor Masashi Minagawa traveled from his home in Bristol, England, and, as guest instructor, developed and taught a curriculum loosely based on the theme “The Sword that Gives Life.” PacShin board members and gasshuku organizers Shin Aoki (Director of Instruction), Derk Richarson (Gasshuku Manager), and Cheryl Williams (Treasurer) presented the theme to Minagawa sensei, inspired in part by the recent passing of beloved Shintaido teachers John Seaman, Joe Zawielski, and Anne-Marie Grandtner, and the naturally arising question of how a community can heal and revitalize itself in the wake of such losses. In Japanese tradition, the sword has been used for the purpose of purification and cleansing, Minagawa sensei explained. When people pass on, the sword is used in ceremony to purify evil spirits and ensure the loved one’s safe journey.

Minagawa Sensei Giving Gorei – photo by Chris Ikeda-Nash

Holding this idea in heart and mind during four keiko—the first taught by Shin sensei, the next three by Minagawa sensei—anywhere from 15 to 18 practitioners cultivated their relationships with bokuto and bokken through a variety of movements, kata, and kumite.

Kenjutsu Kumite – photo by Tomi Nagai-Rothe

These included:

Irimukae. Individually, each of us held our sword like a candle in front of our body, and walked forward and backward. Your body enters the sword, and the sword enters you. The sword and you become one—and move as one. This exercise helps shift our fear of “getting cut by a sword” into “welcoming a sword.” In kumite, two people held one sword and moved the sword like a kayak paddle, in a figure-eight pattern of jodan and gedan cuts, to unify three worlds—the self, the other, and the sword. Elements of martial art, abstract art, meditation, and body care come together in the movement.

Diamond Eight Cut. In preparation, we held our swords with both hands far apart and, following the Diamond Eight pattern, reached up and down, side to side, back and forth, and diagonally to synchronize the sword movement, the body twist, and the traveling gaze. At the beginning of the more formal kata, we visualized the heavenly sword descending and entering our bodies, coming together with our inner swords. Thereafter, every swing of every cut could be done in concert by the physical sword, the inner sword, and the heavenly sword. In unison, we moved back and forth through the dojo, each of us continuously following the Diamond Eight Cut sequence. Eventually, we all started interacting with one another. Some continued cutting precisely, some were swimming through the crowd like fish, and some were dancing joyfully.

Group sword kumite – photo by Chris Ikeda-Nash

An outside observer might have seen the swirl of bodies and swords as the spontaneous manifestation of li, a Neo-Confucian concept that Alan Watts described as “the asymmetrical, nonrepetitive, and unregimented order which we find in the patterns of moving water, the forms of trees and clouds, of frost crystals on the window, or the scattering of pebbles on beach sand.”

Shoden no Kata. This was the first Kenjutsu kata for many gasshuku participants. Slow and graceful, it emphasizes the continuous flow of the sword movement from the beginning to the end of the kata, it demands seamless concentration, and it develops your awareness of every moment of your sword swing.

Without sword, we practiced Tenchi-kiriharai, a karate technique used against a tsuki attack, which helps the attacking partner connect with heaven and earth, and invites investigation and embodiment of a liberating upward-and-downward spiral motion.

Minagawa-Shin kumite – photo by Chris Ikeda-Nash

On Sunday morning, Kenjutsu exams were offered, with Robert Gaston serving as exam coordinator and Connie Borden as goreisha. Cliff Roberts took a “mock” exam for evaluation and received feedback, and Chris Ikeda-Nash performed, passed, and received his certificate for Shintaido Kenjutsu Ni-Dan. Rounding out the morning, Margaret Guay taught an abbreviated keiko that explored deep listening and brought participants into intense and subtle levels of ma.

At one point during Kangeiko, Minagawa sensei talked about our Shintaido practice—and our everyday lives—in terms of walking a path, on which are also treading all those who have come before us and all those who will come after. The majority of participants at Kangeiko, and at the Advanced Workshop taught by Minagawa sensei the prior weekend, were Bay Area residents. But with Shintaido practitioners flying in from the East Coast (Margarat Guay, Rob Kedoin, Brad Larsen, Lee Ordeman, and Elizabeth Jernigan), and with Minagawa sensei coming from England and H.F. Ito sensei coming from France, the gasshuku felt at once local, national, and international. Minagawa sensei encouraged us to invite John, Joe, and Anne-Marie into our practice, which gave the event a spiritually universal feeling, as well.

Between-keiko pot luck brunches at the homes of Sandra Bengtsson and Robert Gaston (during the Advanced Workshop) and Jim and Toni Galli Sterling (during Kangeiko), plus a group Mexican dinner and post-gasshuku restaurant brunch in San Rafael, all served to strengthen and refine the ma between participants, and added to the sense that the sword had indeed given new life to our Shintaido community.

A Recap of the Semi-International Gasshuku in Tirrenia, Italy

31 October to 4 November 2018

By Connie Borden and Shin Aoki

For five days, sixty Shintaido Practitioners practiced in Tirrenia, in the Italian region of Tuscany. From pasta to wine, from early morning meditation to late evening meetings, the group was united in the theme Toitsu Tai. Organizers Davide, Patrizio and Gianni had the vision of each keiko trying to reach the core of Shintaido. They asked the teachers of the subjects of karate, bojutsu, kenjutsu, meditation and open hand Shintaido to show these disciplines as expressions of the same spirit from the deep heart of Shintaido. As Mike Sheets said: “The instructors had us work very hard to find the center of both yourself and your partner. The other reminder was not about pieces of Shintaido but the whole – how they are connected.”

Master Instructor Masashi Minagawa spoke of the theme Toitsu Tai – Unification. Here are his words:

“We (Gianni and I) agreed that when you let go of unnecessary things, only the character ichi- one -Oneness is left. . . .

Ichi – One

For me, this one line contains everything. It is the ‘Line of Life’, the starting line, the goal line, the beginning and the end. It is my Golden Line, The Diamond Eight, One swing of the sword and “Ichi no Tachi” – the first movement of Jissen Kumitachi.”

The advanced group spent the first three keiko studying with Ito Sensei. Chuden no Kata and Okuden no Kata in the kenjutsu program were practiced. In addition, the group selected a few of the advanced Jissen Kumitachi to focus their study.

Advanced workshop group

Minagawa Sensei lead the next three advanced keiko to focus on Jissen Kumitachi #1 to 11. Each morning started with an hour of collegial practice to review the teaching from the day before. Each evening concluded with meetings: the Kenjutsu Task Force, the European Technical Committee, and the general membership meeting of the European Shintaido College.

The last night was a party that included Ula leading ice-breaker activities and Shin teaching line dancing!

High level exams were offered Friday afternoon on 3 November. Congratulations to

- Shigeru Watanabe – San Dan Karate

- Daisuke Uchida – San Dan Bojutsu

- David Eve, Alex Hooper, Georg Muller, Marc Plantec, Daisuke Uchida and Shigeru Watanabe – Ni Dan Kenjutsu

- Shigeru Watanabe – Shintaido Sei-Shidoin/Instructor

- Jean-Louis de Gandt, Serge Magne, Mike Sheets and Soichiro Iida – Shintaido Sei-Shihan/Senior Instructor

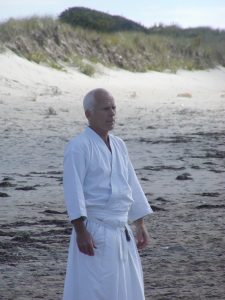

The general gasshuku began Friday afternoon with a keiko taught by Gianni Rossi. Two keiko were taught on Saturday. Weather cleared enough to be at the beach with a stunning view of the mountains to the north and a calm sea to the west. Shin Aoki and David Franklin taught karate.

Shin Aoki teaching in Italy

The second beach keiko was bojutsu lead by Alain Chevet, Georg Muller and Stephan Seddiki. The group experienced an Italian sunset over the water.

Bojutsu keiko at sunset Italy

Saturday morning and Sunday morning, Ito Sensei lead a 6:30am Taimyo meditation.

The fourth keiko was kenjutsu by Pierre Quettier and Ula Chambers. Pierre gave a demonstration with his katana showing Chuden no Kata and Okuden no Kata. Masashi Minagawa lead the closing keiko with open hand Shintaido.

Three masters of Shintaido

The United States was represented by David Franklin, Mike Sheets, Connie Borden, Michael Thompson, Mark Bannon, HF Ito and Shin Aoki.

USA group at Italy semi international

Photos by Marc Plantec.

Ooooo~Uuuuu~Mmmmm~Aaaaa!

by

Master Instructor H.F. Ito

Life is a path. We come from Mu and we go back to Mu. Life is long, and our own lives are each a small part of life. Sometimes rain, sometimes wind, sometime life or death. Pretty simple, actually, it is what it is. Ikkyu

Joe and John. I’m sorry I missed a chance to talk to you just before your departures.

John Seaman

In these days, the more I practice Tenshingoso, the more I appreciate the end of the movement (Oooooo~Uuuuuu~Mmmmmm)!

Joe Zawielski

When I was young, I was practicing this part of Tenshingoso according to the text/recommendation written by Aoki-sensei.

I enjoyed it, and I kept sharing my understanding with many people having the confidence of how much I know about the cycle of our life.

Now that I’m 76 years old, I understand that my grasp of this part of Tenshingoso has been rather superficial.

It is always difficult for me to watch those who helped me share Shintaido leave for the next stage of their life. I wish I could have had a face-to-face meeting and express my gratitude in person.

But, I am lucky that I can still communicate with you, through the following ways:

- Through the sound of Oooooo, I believe that I can reach you who are now omnipresent in the universe!

- Through the sound of Uuuuu~Mmmmm, I can feel you in my Hara, You are gone but I still have many memories of the goodness I have studied from you.

- Through the sound of Mmmm~Aaaaa, I can ask you to appear!

I hope you will continue to share Shintaido, and want to ask you to become our “Guardians” in the sky!

Looking forward to talking to you in Ten in the near future!